In my recent writing about storylet narrative design, I’ve talked about

- storylets and why they are cool

- how storylet systems work together

- how storylet systems can play nicely with gameplay, using casual games specifically as a lens

I’ve also, at other times, written about how I design for pacing in Twine games and parser IF games (in terms of puzzles, maps, and story blockers).

I use similar methods when working out the large-scale design for a storylet project to do the following things:

- Represent the story concept from start to finish

- Distinguish sections of content that are fairly open and player-controlled from sections that are fairly tight

- Distinguish sections that reuse shared parts of the storylet world from sections that are unique to just this narrative arc

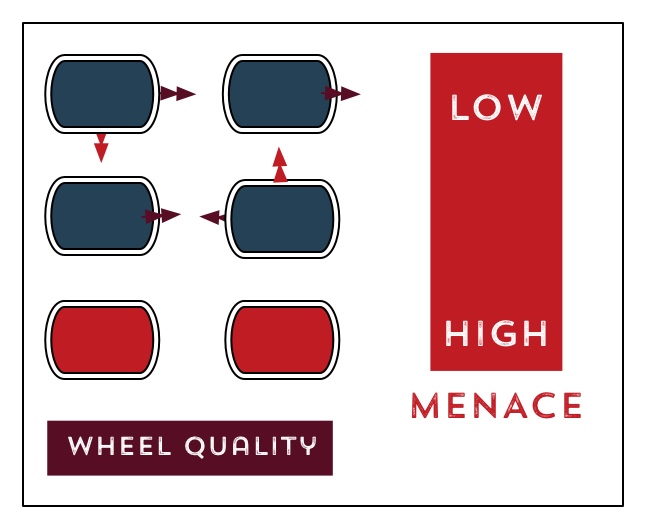

Sometimes storylet passages can be very linear indeed — essentially a straight progression from one storylet to the next.

Alternatively, they can be highly freeform, with a bunch of randomly selected story beats that can advance the player’s goals, move them backwards, or cause/alleviate menaces.

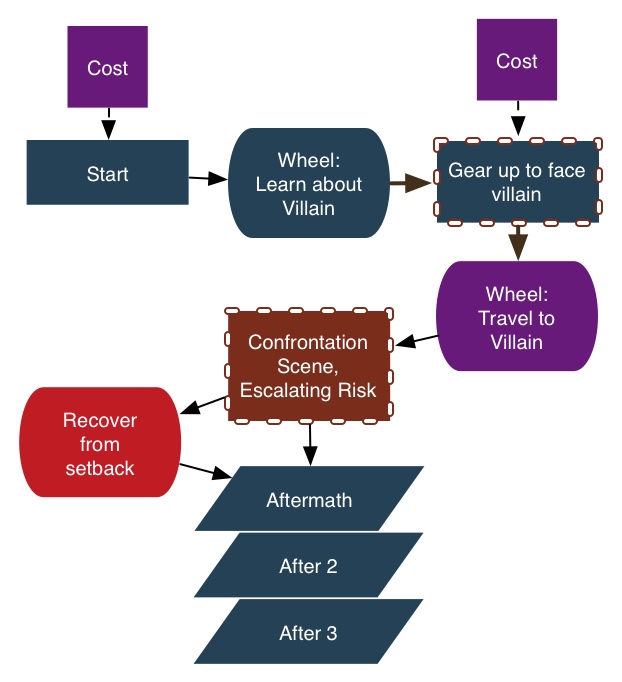

With those things in mind, I make a high level chart that represents these different types of storylet cluster. This is how I might graph out a classic attack-the-Bond-villain sort of storyline:

- Square elements represent shorter set pieces — single storylets or linear progressions

- Square elements with knobbly outlines indicate passages where the player can do multiple actions within a single storylet and has the option to decide when to exit:

- “gear up” lets the player choose how much to spend before deciding she has enough gear to proceed

- the confrontation scene is a risk scene, where more the player tries to gain, the more likely she is to fail

- Round-edged “Wheel” structures represent sections of gameplay where the player is working with a partially randomized deck

- the red menace wheel specifically represents something the player must do to recover from failure — providing a soft gameplay punishment if you push your luck too far and get caught or harmed by the villain, but not preventing you from moving forward completely

- Rhombus “aftermath” elements there are like the squares, but they’re in more of a hurry. These represent storylets that lead straight one into the next with minimal player freedom to create a sense of acceleration towards what will be a cliff-hanger

A lot of the pacing elements common in other types of interactive story apply here. Areas where the player has a lot of freedom tend to feel less intense; more linear, constrained sections are good for climactic moments. Alternating the two keeps the experience from feeling too stale.

There are also some pacing choices about how the design uses elements from other stories or from the game’s system, however.

“Cost” elements require the player to bring in resources from somewhere else. They’re typically slowing features, because if the player hits that point, doesn’t have enough resources, and wants to get them, she may go play another piece of the game for a while before returning here.

That’s good at the very outset of the storyline, and it also works in the cost-linked choice storylet, where the player is deciding how much she wants to pay, in the moment, to increase her odds of winning in that confrontation to come. In that context, I’m effectively asking her to set some mechanical stakes of her own and place a bet about how much an easy success later is going to matter to her.

Meanwhile, the purple “travel” wheel is also using a consistent travel mechanic that turns up lots of places in the game. If this is told via actual storylets, there might be a little bit of customization to make it tell this journey rather than a different generic one — but essentially the player is following a pattern she already knows well. If not, I might be relying on a non-storylet travel mechanic in the game.

Putting this travel segment right before the big confrontation gives us a little time to build anticipation and create a sense of occasion — after the stakes for this particular story have already been set. It wouldn’t have been so satisfying as the first step of the story, though. The story’s up-front hook needs to be new content.

Resources

- I’ll be giving a talk about developing with storylets at the London IF Meetup January 29. It’s free, and those in the area are welcome to join. We’re also working on getting it recorded, thanks to a volunteer, so hopefully I’ll be able to share that around as well.

I’m trying to work out how using these tools would work in practice. Could you give a specific example of an issue you spotted by plotting out storylets like this? (A made example up is fine, but something concrete.) I’m especially having trouble visualizing what a “bad” diagram would be. (Like, in this spot in Fallen London, we found this particular piece of plot was too linear [what would be the threshold on this?] and so we replaced [this bit] with [this bit].)

(…also, given you posted that puzzle chart from Counterfeit Monkey, that may be in fact your exact follow-up later, but as it is I have trouble looking at it and glomming on some specific design decision.)

Samples, vague or slightly anonymized:

– Realizing my initial concept for a story had one wheel leading directly into another, which was going to feel slow and sloggy to players, and that it would be good to interrupt that transition by adding some intervening linear, story-specific stuff.

– Realizing that I’d put a cost on a part of the plot where I actually wanted the player to be accelerating.

– Realizing that I was overusing general-purpose wheels and they were going to make the story feel too anonymous.

– Realizing that a story that was supposed to feel focused was also going to unlock an only-semi-related side quest halfway through, which was fine in theory but would be likely to distract players; therefore, moving that side quest unlock elsewhere.

It’s all stuff you could reason about without the aid of the picture, but the picture makes it jump out, and it’s helped me find likely problems without going through the “implement, play, iterate” cycle first.

“cost on a part of the plot where I actually wanted the player to be accelerating” sounds especially tricky to catch without the visual.