I used to publish questions that people have asked me either by email or on Twitter. That went on a hiatus for the past year-and-a-bit, as I’d stepped back from blogging for a time. To kick off something similar again, I asked Twitter folks what they’d be most interested in seeing me write about.

One of the requests was an article on how to provide NPCs with enough agency that they’re not place holders for plot points.

Despite the terms here – NPCs, agency – this is not necessarily a question about AI, character modeling, or even game design generally.

This is fundamentally a plot question. If you want active, agency-holding characters, that means knowing which character wants what – or which character fears what; how they’re trying to get it; and what incidents happen as a consequence. Only sometimes do game mechanics or tech come into it at all.

Plotting is one of the most invisible kinds of work you can do on a story. Beautiful sentences, funny dialogue, worlds with striking and memorable setting ideas: readers can often identify what they’re looking at when they see those things, and aspiring writers have lots of comprehensible examples to work from.

But plot’s harder to see in that way. It’s structure, not surface. It’s everywhere and nowhere.

Even when people do talk about plot in things they’ve read, it’s very often to remark on a plot hole, a defect in the story’s causality or internal logic. Experienced readers might also call out beginnings that don’t hook the reader; endings that feel sudden or unearned; pacing that drags; scenes that don’t change anything either about the state of the world or about the reader’s knowledge thereof.

But good plotting is about more than simply avoiding those defects. Often a truly outstanding story will have some aspect in which it doesn’t stand logically stand up. It can still be a great piece of work, and even a great piece of plotting, as long as that nonsensical area wasn’t doing any important work in achieving what the story needs to achieve.

Plot is to blame for so much, really

Driving active NPCs isn’t the only plotting problem people are running into. Quite a few of the other questions from Twitter were also how-to-plot questions, even when they don’t self-identify that way:

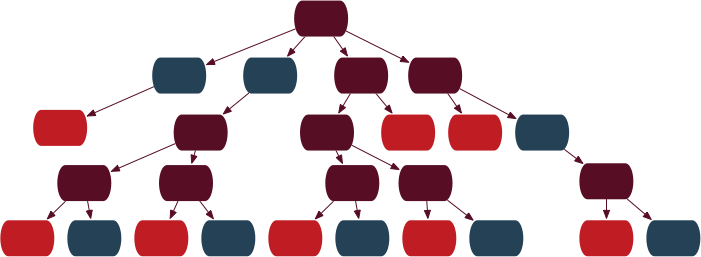

- outlining, both overall and scene/segment specific (subsequently clarified to mean “how to figure out the structure of a branching narrative”)

- Merging narrative branches so as to keep the total amount of chaos from being visible from outer space? Which paths can you merge, which do you drop or cut short, or which should you perhaps not even pursue at all

- Endings. Like, what. How.

- To which someone else added, And beginnings. And middles.

All plot questions.

The struggle I see running through all of these isn’t really about the shape of the plot, in the way we talk about three-act structures, or about rising and falling action. It’s also not primarily about scene types as building blocks.

It’s about choosing the incidents themselves — what happens? — and the causal links between them. It’s the set of questions we find prompted in the “story spine” prompt often associated with Pixar:

Once upon a time there was ___. Every day, ___. One day ___. Because of that, ___. Because of that, ___. Until finally ___. And ever since that day, _______.

Variously attributed

If those causal links connect to things that the characters want and things that they’re trying to do, then the plot is rooted in character agency.

Meanwhile, on endings: figuring out the “Until finally” beat is often a really painful one. Especially if we’ve done a solid job during the beginning and middle of the story building a convincing, deeply-motivated conflict, it might now feel impossible to come up with any solution that will end the quandary.

All the branching is what makes this painful, though, right?

I don’t think so.

Sure, it feels like a branching narrative is necessarily harder to plot than a linear narrative, especially when you’ve made some ink or Twine monster and are staring at not one but a dozen unfinished trajectories of story. (See also veteran novelist Max Gladstone talking about his outlining when he started writing for interactivity.)

But in my experience, what’s really going on here is not inherently a problem about branching. The problem is that being allowed to branch your narrative means that, as an author, you can postpone the reckoning.

Don’t know which of two ways you want something to go? In a linear story, you’d have to make an artistic choice here and decide where your characters are going and why. But with an interactive story, you don’t have to! Branch time! In doubt again? More branches!

Still, it’s hard to write your way out of needing a plot entirely. Sooner or later you need to bottleneck your story again, or prune your branch structure down to a scope you can write, or decide how to end all the different trajectories that you’ve permitted to explode outward from your premise.

And when you do need to resolve those problems, all those branches you wrote without quite knowing where they were going – those all become liabilities.

Plot and theme

By contrast, if you have a plot in mind from the outset, it gives you a structure for interrogating and understanding what your branches are doing there.

You may know, for instance, that the story is themed around the difficulties of building a just government, and that the crisis moment of the plot is going to involve a conflict between several contenders to lead a newly-established community.

Now we can ask: what choices are going to lead into that crisis in interesting ways? Can the player choose individuals or ideologies to support before the crisis comes? Can they build up resources that might affect the conflict, or that might mitigate the consequences if things go awry?

Or maybe we’re worrying about branches on a somewhat less macro level. Maybe it’s not “what are the big variants” and more “should I have this one option.”

Having a plot in mind helps there too. If I know what the bottlenecks are going to be in my branch-and-bottleneck structure, I can ask myself what work this branch is doing to

- move me towards the next bottleneck

- set up the stakes for the choice I experience there

- give me a perspective on that choice, or resources, or options, that I wouldn’t have if I’d taken a different branch

(Before anyone asks: “we have to have that option/branch because the protagonist could theoretically do that thing” is not an overwhelming reason to have a branch. There are many ways not to give the player a branch even if the protagonist would, theoretically, have a choice in that location.

There is a slightly stronger argument if you’ve mechanically established an expectation that the player will always be able to use a particular verb; in that case, it might feel like cheating to take it away in particular circumstances.)

Surely interactivity has an impact on this somehow?

In my experience, yes — but the way it works actually replicates an issue in linear plotting.

I mentioned earlier that endings can be a pain if you’ve done all your good authorial work to set up a strong conflict but not figured out what could possibly resolve those conflicts. It’s like constructing a locked room murder mystery where the locked room is just too robust.

A common way through that is to think while plotting: which aspect of this conflict is effectively under the protagonist’s control? What could they choose to change that would resolve it? And what could plausibly motivate them to make that change?

For instance, for “Matchmaker” — a short audio piece I wrote for Zombies, Run! — I wanted to write something like romantic comedy, but covering a later stage of the relationship than the meet cute: I wanted to talk about two people who’ve already been in a relationship for a good while and know each other well, but still have challenges to overcome before they finally commit.

So I needed an incident that would drive them apart for a time: something

- unexpected enough that the characters couldn’t have anticipated it it

- serious enough that it would make both characters doubt their relationship’s survival

- not so big that it couldn’t be resolved within about half an hour of audio

- not so fraught that it would take the story out of romcomland.

And it needed to be something that would give both of the two romantic leads a significant part in the emerging tale; I wanted it to be a real two-hander story, not something where one of the characters is purely a backdrop to the other’s decision-making.

Figuring that out was, honestly, a real pain. Even though I knew what kind of thing I was looking for — what effect the incident should have on the characters, what tonal level it should be at, the social and cultural setting of the story, and a bunch of pre-existing work on the characters themselves — I spent a lot of time brainstorming, scribbling in notebooks, staring at walls, and running various ideas past both my husband and my brother before I landed on something I felt worked.

When you’re dealing with a plot issue like that, it sometimes feels like you might never succeed: it’s a process of searching, not of constructing.

Is there something that fits into the negative space made by the rest of your story? You hope so! When exactly will you finally think of that something?

It’s a hard problem in interactive story… but mostly it’s the same hard problem

That was a linear story. I’ve had almost exactly the same type of challenge with interactive stories. The main difference is that, in the case of interactivity, I revise that arc question to “Which aspect of this conflict could the player affect? If the story is mainly about an NPC, where are the openings for player influence? What verbs would the player be using to cause those effects? What are the consequences if the player pushes in one direction or the other?”

Ultimately, a lot of this leads back to the same kinds of questions we might ask when figuring out what stats or state tracking to use in a particular project. What cumulatively matters to this story world? Which aspects of the theme do we want the player to be able to explore interactively? What kinds of relationship impact can the player have? Once we know the player’s potential scope of action, we can start to imagine ways that they could inflect a character’s story arc.

All those are constraints on the possible plot incidents. But at the end, at least in my experience, solving a plot problem like this, linear or interactive, still comes down to the same things:

- searching your whole entire brain, and possibly also the brains of your fellow writers, friends, and/or partner, until you find something that works; or

- deciding to back up and change the constraints by altering an earlier scene or two.

Actually there’s another thing that’s often hard about game plots

Communicating the idea to the rest of the team? Making sure the animation budget can afford your ideas? Aligning your concepts to the existing level design? Navigating any marketing pressures or scope changes?

Okay, yes, all those things. But the one I’m thinking of is time. Movie scripts spend eons in development; novelists often rework their darlings for years before going to press. But unless you’re writing something extremely indie where you control the release date completely, writing for games tends to be a lot more compressed — more like writing for episodic TV or something where there’s an actual scheduled time when something has to be done.

You need to have your good plot idea and you need to have it by tomorrow so you can make your deliverable/close your ticket.

Episodic TV often handles that by having a writers’ room, because if a major bottleneck in your plotting process is thinking of the right beat breakdown, then it helps to at least throw a whole bunch of thinking at that problem simultanously.

Game studios do not necessarily have a writers’ room either. Some do — I’d say it’s increasingly common. But there are a lot of game writers working alone — as solo creators, or because their studio has hired exactly one writer, or because the way their work is divided up silos everyone into separate chunks of content, and there’s no time or opportunity to share or ask questions.

At least that last point is something that can be changed, even informally. At Failbetter, we do have a specific person in charge of each story we build, but we also have time set aside for people to talk through any writing blockers they’re currently confronting — and every writer on the team uses that opportunity freely, regardless of their seniority or what kind of storyline they’re working on.

If you’re at a studio that does have a bunch of writers but doesn’t have a culture of sharing brainpower on problems like this, it’s definitely something to explore starting up.

*

There’s a huge amount more to say about all these issues — about how to pay attention to plot in other people’s work, more strategies for tackling plot knots yourself, stories of specific struggles. I’ll stop here, but if time permits, may address some of those other points in the future.

For now, some links.

Related reading about visualising plot within a branching narrative:

- Twine Gardening

- Writing for Varytale (the multiple levels of visualisation here being a key point)

About theme or thesis and plot:

About characters and plot:

- Small Plotting Trick for Choice-of Work

- Designing Characters for Mask of the Rose

- Write Characters Your Readers Won’t Forget

About mechanics/level design and plot:

- Plot-shaped Level Design

- Plotting for Interactivity – the Set-Piece or Crisis

- Montage, Narrative Deck-Building, and Other Effects in StoryNexus (this gets a bit into gameplay equivalents for montage sequences)

- Plot, Scene by Scene (this one is pretty old and assumes that you’re writing a text adventure; it’s also probably not how I would now break things down)

About running a writers’ room for games:

- Gamasutra article from Gabriel Padinha

- Zack Gariss on running a writers’ room for Life is Strange

- Venturebeat video on putting together a good writers’ room for AAA games (Derek Kolstad, Adam Foshko, Mark Long)

Hi Emily, thanks for the post.

I cracked at the part where you describe branching as a way of evading choice-making for writers; so true it hurts.

Also, I don’t think time constraints or tight deadlines are exclusive to the game industry, nor particularly harsh there. A couple of days ago I was listening to Halley Gross on Thanks for the Knowledge podcast, and she was talking about how she had a lot more time to work while on Naughty Dog for The Last of Us II (four years) than for Westworld or TV/film in general in Hollywood, where projects are short-term and you’re usually on it for 10-12 weeks or at most one year, you deliver the work on deadline and you’re done.

So regarding “You need to have your good plot idea and you need to have it by tomorrow so you can make your deliverable/close your ticket.”, don’t you think that’s the case pretty much always if you’re working as a hired writer and not on a personal project, in whatever medium?

I liked the thought about how branching narrative can sometimes be a crutch. Sometimes what feels like a stylistic/mechanical choice turns out to be a method of delaying authorial decisions and it’s difficult to be honest about that.

What a great post that really focuses on character choices driving plot, both in linear and branching narratives. That Max Gladstone article you linked was superb as well.

Thank you for this! As someone currently writing both a branching narrative and a more linearly driven narrative adventure, there was so much here that really spoke to roadblocks (both potential and current) on each project and how I can overcome them through my characters. I really appreciate this, and look forward to the next post!