Making of “Bronze”

The brief: Bronze began as a Speed-IF, a game written in two hours. The premise was to take any fairy tale (in whole or in part) and retell it with a bit of a twist. Subsequently, I decided to take this lightly-implemented shell and try to extend it into a game with more solid puzzles and backstory, but maintaining the expansive geography and sparse object distribution of the original.

Initial Speed-IF

Speed-IF is a light-hearted competition in which the contestants each write a game in two hours. As might be imagined, the results tend to be a bit sketchy. Nonetheless, the exercise of coding a winnable scenario in two hours can be useful.

My initial idea was that I would re-tell Beauty and the Beast, and — just as a departure from my usual approach — I’d make the game map very expansive but very lightly implemented: only a handful of items per room, with short room descriptions and minimal simulation for the objects. That would allow me to focus the player on moving around the map. What I wanted was to reproduce the fairy-tale sense of a very large, very strange space that — when the Beast is gone — suddenly feels quite empty.

Most of those first two hours of implementation went to writing room descriptions and connecting up the map. At this point, Inform’s syntax and map index became extremely handy: I wrote a few rooms, compiled, looked at the map index, decided where I wanted to add more rooms, etc., until I had constructed a large space.

To make sure that plenty of wandering happened, I arranged the code so that the Beast would only appear after the player had explored at least half of the game’s fairly substantial map.

As I did this, I came up with a sketchy backstory to explain the situation: the Beast inhabits a castle that enslaves everyone who walks in, with or without the will of its owner. Not only that, but the castle was owned by a line of kings who had the power to enslave people in eternity, even after death, so that the spirits still haunt the castle and provide food and so on.

Given all this, the player might have two goals: reviving the Beast and freeing his servants. So on the initial writing, I wrote one way to do each of these things: get food for him using the gold bell to command his kitchen staff; or get vengeance on him using a bronze gong that summoned an angry demon. I also added the silver bell, contract book, and reading room so that the player could find out a little information about the player character‘s own history — though at this point the contract book was pretty simple.

Player Experience

The first thing I did when I decided to expand Bronze beyond its Speed-IF state was retrofit it with some conveniences for the player. The map isn’t a huge one in an absolute sense: at 51 rooms, it’s a bit bigger than Infocom’s Witness, but considerably smaller than Enchanter (at 74) or Zork I (at 110). But it is a large map for the amount of game that happens in it, which means that the player will spend a lot of time trying to make sure he’s seen all the available rooms, and then walking back and forth across the map to get things.

To ease the pain of this, I borrowed a few items from examples in the Inform documentation: a GO TO action that allows the player to move automatically; a FIND action that allows him to retrieve articles left elsewhere; a status line that shows a compass rose with unexplored rooms marked in red; and PLACES and OBJECTS commands so that he can review what he has and has not already seen.

I also built in an adaptive hint system using the documentation example, allowing the player to ask for hints about any object or room in the game.

Expanding the Puzzle Structure

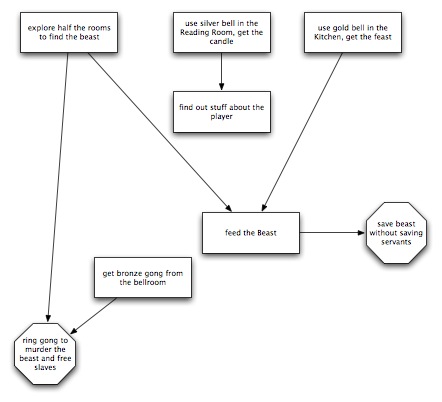

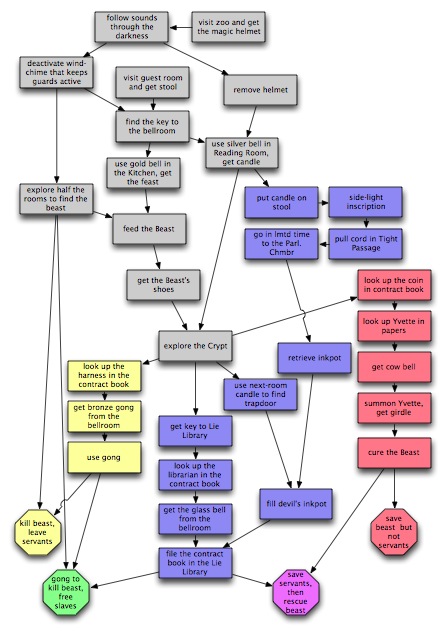

The next step is to consider how to expand the game productively. Here we have a basic puzzle diagram of a very early state of Bronze. (Normally I don’t make these diagrams in a diagramming program, but I do scribble them on a notebook next to the keyboard.) The diagram shows each step the player must follow to get to any given ending. There are several endings available, depending on whether we want to punish the Beast or save him from himself.

Not so bad for two hours, but from a story-telling perspective, this structure has problems. The contract book, one of the most interesting items in the game, is not required for either ending, so the player might breeze by it entirely. Meanwhile, the bronze gong is stored openly in the Bellroom, so it’s possible for the player to find and use it without ever learning its purpose.

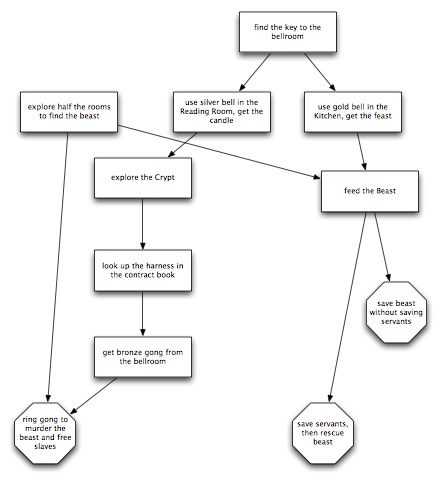

A natural preliminary would be to put this information in the contract book — and then refuse to let him use the gong until he’s read that passage. So let’s say that some of the bells in the bellroom don’t become available until the player has already read about them. That makes sense: we’re told that the room is full of bells, but we don’t recognize all of them.

The player will need the candle in the reading room to read the contract book anyway, but we’ll also protect the secret of the elephant harness by putting the whole Crypt area in darkness. This is really for the player’s benefit: it will stop him trying to use the things down there (which are only interesting once he has the contract book) until he has solved the light puzzle. Thus we cut down the number of leads he has to follow at a time and make sure that he discovers information in a somewhat sensible order.

And, while we’re at it, we’ll put a lock on the Bellroom door to ensure that the player has navigated other parts of the map before he gets there. We don’t want him ringing any of the bells too early.

I also want to add another ending — this structure doesn’t have what you would call a happy conclusion yet. We want to be able to destroy the contract book in some way that doesn’t involve the Beast’s death. I considered some boring approaches (burning it, tearing it up), but those are too mundane for such a powerful object. Then it occurs to me: what happens if you check something true into the Lie Library? The Lie Library was a room that I added more or less at random during the Speed-IF phase of creation, but now I find that it strikes my fancy.

So let’s add the possibility of checking the contract book in here. To do this, we will need to summon the librarian. And let’s say that the librarian can only be summoned with a glass bell, which we find through the contract book.

With this puzzle arrangement, we still have the problem that Crypt exploration becomes unnecessary unless the player wants the bronze gong. (And it seems safe to say that many players won’t want it, or won’t think of trying it.) We’d like the player to at least encounter the elephant harness, even if he gets no further than that.

So how about adding in a puzzle to force the player to see what’s in the drawer before using the Lie Library? The easiest structural approach is to seal the Lie Library off. We’ll give it an ivory door and key: an ivory door is traditionally associated with false dreams, and an ivory key would go nicely in the same drawer with the elephant harness.

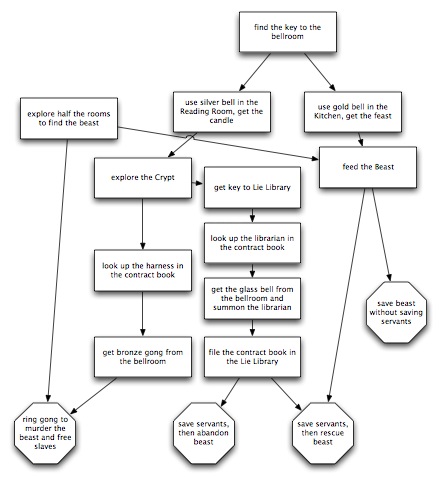

My next concern is that the branch with the feeding of the Beast (if we don’t also save the servants) is very short and not very interesting. Besides, I’d like to sneak in some more backstory about how the Beast got to be like this.

What to do about that? Add a whole additional puzzle: he’s been made into a Beast, after all, so what if we also have to do something to free him from that condition?

Traditionally the cause is an enchantress who punishes the Beast for some unkind act — selfishness, or failure to see beneath a person’s appearance. But I had a more specific history in mind: the Beast’s particular crime is that as a young man he used to bring women he fancied to the castle, whereupon they would be unable to resist his wiles. One woman so brought turns out to have magic powers of her own, and when she realizes what is about to happen to her, on the drawbridge before the castle, she casts this curse on him.

I don’t want to completely remove the elements of the original tale: we’ll keep the kiss as an element of the puzzle. But there has to be more to it than that. Perhaps the player needs to be wearing something unusual: I recollect a business with a magic girdle from Sir Gawain, which has the right flavor for this story. So we say the player has to have that. We also say he has to get it by consulting with the spirit of the dead woman who cursed the Beast, by scrying in one of the mirrors. That gives us an excuse to require the player to find an object in the Crypt area, look it up in both the contracts book and the paperwork, and then use the hint in the Scrying Room to perform the actual summoning up in the Bedroom — making good use of several parts of the map that have previously been neglected, and guaranteeing that he does use the papers at least once.

This is starting to get complex, so for the sake of clarity, I also colored the nodes that the player MUST experience to get to any one of the endings:

From a structural perspective, things are starting to look up. There is a lot more to do in this game than there used to be, the player is more likely to see all of the important junctures, and we have enriched the map. Some of the puzzles are not especially novel — I wouldn’t mind replacing any of the locks and keys with more interesting problems for instance.

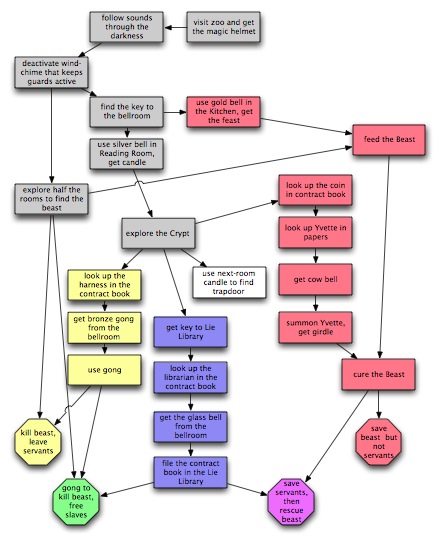

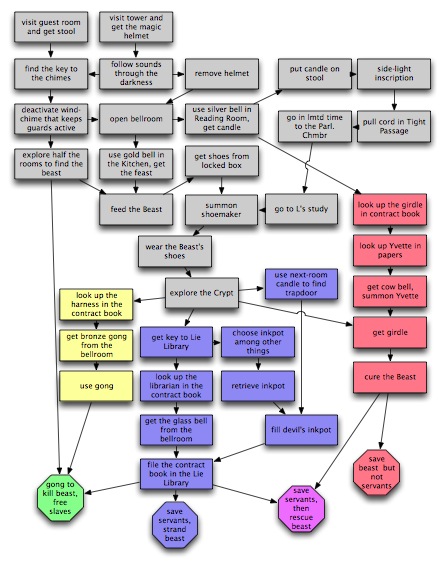

To this end, I have two puzzle ideas I’d like to work in somewhere: one, that you can find a trapdoor in the crypt area by placing the bright candle in an adjacent room (and casting a raking light over the floor, illuminating the otherwise unseen outline); the other, that there are spirit-guards on certain passages, who can be eliminated if the player stills the windchime that is summoning them.

The guards idea is good for early in the game: it will let me set a large area as off-limits. Might be a good way to keep the player from exploring the really powerful rooms — the law library, the reading room — until he has been to much of the rest of the castle, and it would stand to reason that those powerful places would be the ones under spirit protection. So I set a region of the map and rule that the player can’t enter this region while the windchimes are in play. (Because the windchimes rule is tied to a region rather than to a specific door, I don’t have to worry that I’ll introduce bugs if I later create more entrances to the sealed area: no matter how many ways in there are, they will all be subject to the same restriction.)

But what should the player see first? Well, let’s say we’d like him to visit the zoo area, the kitchen, and possibly the upstairs: enough that he’s had a bit of a hint of our life with the beast. So I’ll put the chimes in the rose garden, and make it so that the player can only reach this point by traveling through the dark rooms of the Crypt. This raises a further problem: I don’t want the player to have to thrash around down there in darkness. He might stumble on the right way out, but then again, he might not. So let’s make it so that the windchimes are audible, leading him in the right direction, from inside the maze; and also that a magic helmet in the zoo allows him to hear them for more rooms, so that they’ll be audible right from the first room he steps into. So that gives us this…

Notice the trapdoor puzzle is still sort of free-floating at this point. I haven’t decided what to do with that yet, but I like the idea, so I’ll keep it in there.

At this point I also decide I want to restructure the endings, because some of them are still more difficult to reach than others. How about saying that the gong brings revenge on the beast, but does not free the servants? Then we get:

…a somewhat more balanced distribution of outcomes. I’ve redone the colors again here to show myself which endings are requiring the most work.

I like this raking-light trapdoor puzzle, but I’m worried that it’s going to be too hard, wherever I ultimately put it. Maybe it would help to give the player a little (better hinted) prior experience with using indirect lighting in the dark rooms; so it occurs to me to add a puzzle about reading the inscription on the wall. This is going to require both the candle and the stool.

While I’m at it, I’ll add a prior, easier use for the stool as well, to help the player get the idea of using it as a portable height-increaser:

Now, I think I’d like to add the raking-light puzzle to the strand involving the contracts and the Lie Library. For one thing, that strand is an important one, and it currently feels too easy; and I’d also like the person who solves it to have spent a little more time with the idea of the contracts, learning how the family came to have this power in the first place. So I add a study for Lucrezia down in the Basement area, with an inkpot; and I make filling the inkpot the quest solved by entering the trapdoor. So:

And at this point I also spend a while fussing with the map: moving the Reading Room upstairs, for instance, and making the hourglass rooms the means of access to it. This has several intended effects: one, to make the player take off the helmet (so that he will have to put it back on when investigating the trapdoor — I want that to be a solution worked out, rather than one stumbled over); another, to compact the use of space on the ground floor and make more rooms on the upper floor, for balance. I moved Records upstairs too, while I was at it; and added in the still life gallery and the white gallery, as conceptual balance for the scarlet and portrait galleries, and in order to offer a little more backstory about Lucrezia.

At this point I’m becoming less concerned about adding more puzzles (we have a fair number now, at least for the size of game this is meant to be) and more concerned about story. The puzzle structure makes it likely that the player will find out about Elzibad, Lucrezia, and Yvette, the three main elements of the backstory I want to tell. There’s less here about why the player should want to save the beast, though — less of their relationship. I’m also concerned because, after an initial quest to find the Beast, he becomes more or less a non-entity (interactively speaking) for the remainder of the puzzles. We don’t need to do anything more with him after he’s fed and before the curing, which is likely to leave a lot of time wandering through the Crypt not doing anything with him. And that seems unbalanced, motivationally speaking.

At this point I thought: what if in order to go to the Haunted Area, one needed the pair of the Beast’s shoes? I’d already put a pair of cloven shoes into the Lucrezia still life upstairs, and they are the only magical implement from that image not to appear in the game. These shoes might also allow you to experience some small measure of the Beast’s own feelings about the rooms you visit. This may produce a little sympathy for him. Even if it doesn’t, it will keep his personality and presence constant throughout the player’s later explorations.

I like this idea, but if I make the shoes a prerequisite for Crypt-visiting, what do I do with the inscription/cord scenario that is the current prerequisite? Well, we could always make that the requirement to get into Lucrezia’s study, instead…

I now had a set of puzzles I liked and a bunch of story material, enough so that it wasn’t possible to deduce what was wrong by reason alone. Time for some alpha-testing.

Puzzle Review

Next I played through to each of the possible conclusions to make sure that the puzzles worked as intended in the diagram, and to build a usable skein.

As I did this, noted things that bothered me. One: it was possible to get the Beast’s shoes and the candle in such an order that we never notice the shoes are necessary to get into the Crypt section. This seems like an opportunity for some further elaboration, perhaps another puzzle. Addressed this by adding the shoemaker, providing an extra purpose for the empty bedroom and an extra article to look at in Lucrezia’s study.

There was now sufficient distraction that it didn’t feel like looking up the coins and harness in the contract book was obvious enough. Addressed by adding a line to the harness description, to encourage the player to look it up.

The inkpot was presented a little too baldly (just found sitting there in L’s study).

There was very little in the area around the Lie Library.

Alpha-Testing

The puzzle work up to this point was the effort of a weekend of fairly steady application. Then I set the game aside and came back to it as a player for a number of shorter evening sessions, two or three hours each. This I find a critical part of my writing process: wandering through the game, trying to forget what I know about what’s been implemented and simply interact with it as though I were a new person coming to the game fresh. What do I expect to have implemented? What do I try to examine? How do I feel about the pacing, tone, and motivation?

Most of the changes at this stage were individually trivial: room descriptions revised, objects moved to more interesting locations, hints tested, lots of extra messages added for specific actions. I added quite a few specific memories to round out the backstory, and came up with functions for a handful of rooms that were still placeholders. The Black Gallery entered the game at this stage, as did the Apothecary, the Burnt Frame, and the Smoke-filled Chamber: I had become more interested in the question of what the Beast did between the time he was cursed and the time you arrived on the scene, so I added these elements to hint at his unsuccessful suicide attempts. Instead of having Yvette indicated by a coin, I put in the miniature that is in the game now, and wrote more content around it, as well.

Revised puzzle chart looked like this:

Beta-Testing

Finally I put the game into beta-testing, requesting that testers send me a summary of any problems they found, from outright bugs to deficiencies in the puzzle design; I also asked for transcripts, which allow me to comb through people’s play experiences and see where they got hung up on something that I didn’t intend to be difficult.

This led to a lot of added synonyms, new commands, and similar adjustments; it also became clear that I hadn’t provided quite enough hinting about some of the puzzles (such as the raking-light puzzles with the candle, and the fact that Yvette could be summoned to the mirror). So much of what I added at the beta-stage was what one might call significant scenery: objects, images, and memories that might lead the player to a better understanding of what was going on. This phase lasted about two weeks, with a couple hours’ worth of work processing each set of transcripts as it came in. We tested two copies and then I sent out a release candidate for final comment; the game as released wound up much like that candidate.

Extras

During this period I also constructed the extras for the game. It didn’t seem to need feelies, exactly, but since it is so novice-oriented, I thought perhaps it should come with a manual. I also decided to furnish it with PDF maps (one spoilery, one not). To make the map that comes with the game, I used Inform’s EPS export, setting all rooms and connecting lines to be fairly large and white; that meant that when I put a black background behind these objects, the result already resembled a primitive floorplan. I then cleaned up the results in Adobe Illustrator (reshaping some rooms, making the staircases wider, applying warp-effects to the underground rooms) until I got the current maps.

The manual also includes a list of commands — based on the action index — and a sample transcript. I always feel a little uncomfortable writing sample transcripts from the top of my head because there is a real chance I will forget or misrepresent some key piece of library behavior. So I mocked up a short scenario as an extra “chapter” of the Bronze code, played through it, and copied the transcript into the manual. Because of Inform’s code style, it was easy to add Igor and his environs for the duration; all the pathfinding and similar code from the real game were thus applied to Igor’s scenario as well.