Heaven’s Vault is a game about piecing together meaning from atom-sized pieces.

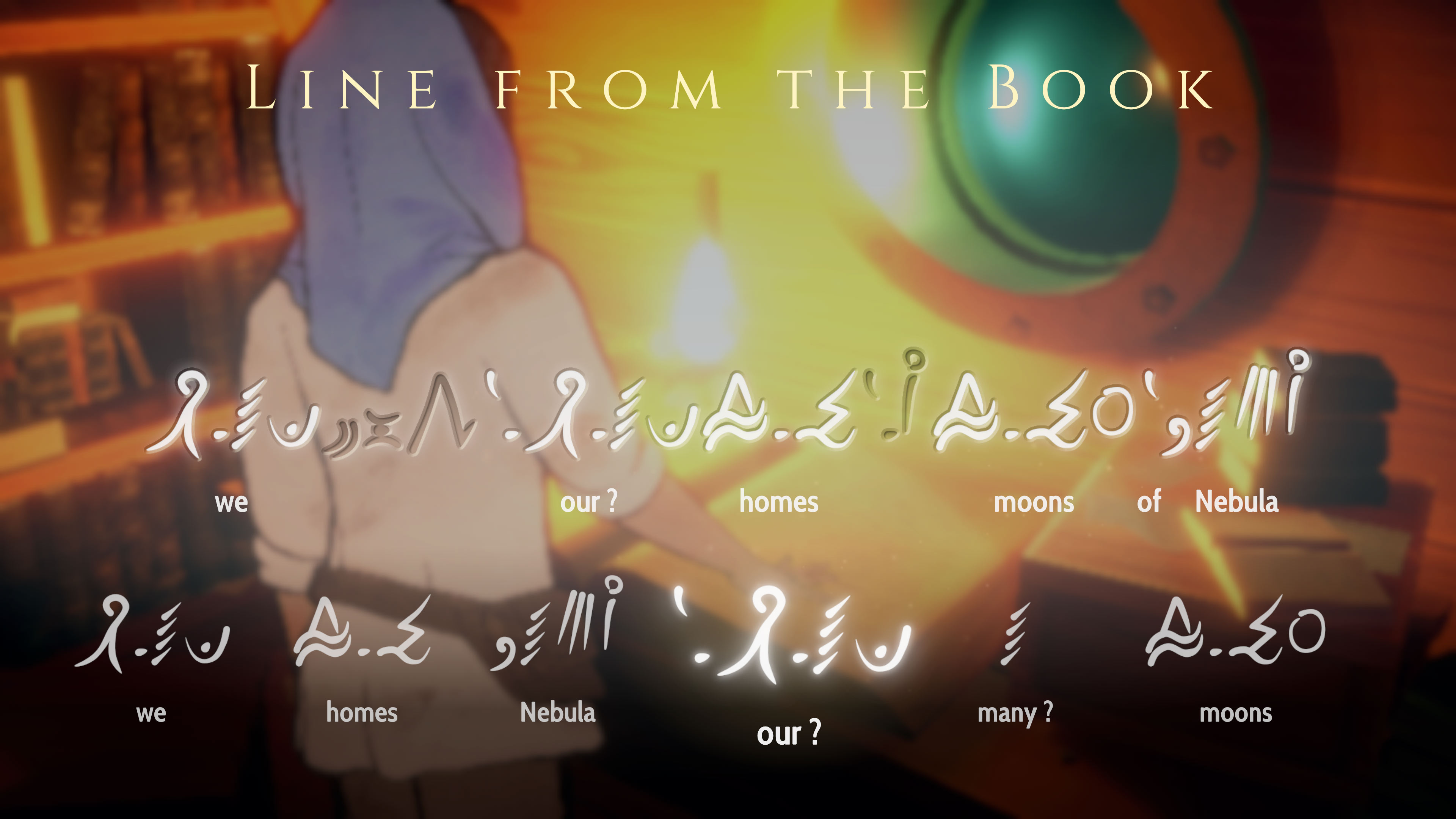

The game’s chief mechanic involves translating inscriptions from Ancient, building a larger and larger personal dictionary until you’re able to interpret entire passages of scripture and significant warnings.

This mechanic is highly satisfying, especially during the early phases of the game. Words in Ancient are made up of a small number of primitives joined together, so as you guess at the meanings of words and sentences, you’re also developing an understanding of what the primitives stand for, what marks stand for nouns or verbs or changes of tense. The more inscriptions you find (and pretty much everything in the Heaven’s Vault universe seems to have a phrase or two of Ancient scratched onto or sewn into it) the more you’re able to decode. Like a crossword, it lets you use leaps of insight in any one area to shed light on others. And because you’re uncovering text, new inscriptions frequently offer new narrative insights.

I really, really enjoyed doing this. While the language of Heaven’s Vault is pretty much encoded English and doesn’t feature the ambiguities and alternative world views embedded in real foreign languages, the process of learning to read Ancient lit up the same parts of my brain as other forms of translation; so much so that I found myself identifying a sequence that meant “voice” and thinking, φωνή.

The game has some pacing issues, noted by other reviewers, and those pacing issues did affect my experience. And by the end of the first play-through, I wished the decoding mechanic would change up and let me make more extensive types of guess on my own, because frequently I “officially” was unable to read something whose meaning was perfectly obvious to me in reality.

Even so, decoding this game kept me onboard for more than 15 hours, at a period in my life where I have relatively little available time for playing anything and have to be extremely picky. And if you replay, you have a new game+ option that starts you over with your existing language learning intact, an accretive PC trick that allows the protagonist at last to feel like she actually is an expert in her chosen field. So if you feel you might also enjoy a translation adventure game, do try it out.

I wish to emphasize this point because I am now going to go into a mass of detail about what I think might have worked better if it had been done differently.

But that’s because this is a really interesting piece of work pioneering comparatively unexplored areas of puzzle design and narrative structure, and it’s at its most instructive when we look at what doesn’t quite work.

Archaeology

A bunch of the reviews say things like “this is the first game about archaeology that actually feels like archaeology.” And it certainly bears a much greater resemblance to archaeology than does Tomb Raider, without being that much like working a dig site or trying to decipher an ancient text in real life.

During play, I started to imagine what the game would have been like if the sluggish, low-stakes travel sequences had been replaced with an exercise in interactive stratigraphy.

I could see from a game design perspective that these sections provided a sense of scale and gravitas to the Nebula, which otherwise might have seemed a surprisingly small place; but the travel itself conveyed little challenge, excitement, or danger. In 80 Days, most journeys probably won’t kill you, but you can still screw up the logistics in ways that will affect the rest of your trip. In Heaven’s Vault you can miss stopping at a ruin if you’re not careful, but you can always loop around (if tediously) to try to reach it again. Then, too, there are some games, like Wheels of Aurelia, where the driving experience is meant as a backdrop to an interesting conversation. But in HV most of the dialogue that happens while you’re on the rivers is pretty lightweight, not enough to sustain the sequence on its own.

Also, here the lack of danger in travel caused some ludonarrative dissonance. Most people in the world of Heaven’s Vault do not travel to other moons much at all, and it’s implied that that’s because the process is risky and very much dependent on the configuration of the rivers. But one doesn’t actually experience that in the gameplay to any meaningful degree. There is one point at the very end where the changing of rivers locks you out of returning to certain places, but up until then, the rivers of the Nebula actually felt significantly less threatening than the average California freeway.

Honestly, I think mimetic travel is often a mistake in story-driven games and I would seriously encourage designers to at least consider whether it’s lending anything to the themes or the emotional experience of the story to make the player walk, run, ride, or sail from one bucket of plot to the next; or whether it would work to substitute in a different spacer activity, or handle travel as a montage of events instead of an analogue progression.

Accordingly, in Heaven’s Vault I started to wish that the spacer activity had been, well, conducting something closer to a real excavation. What if you actually had to dig up all these items and make guesses about them based on the context in which they were found? If there were a risk of destroying objects or losing information if you worked too carelessly? That would have introduced an element of meaningful risk and potential loss — which does exist in archaeology — without killing off the player character.

Linguistics

The handling of language is another place where I enjoyed what Heaven’s Vault had to offer, found it novel, and wished it had gone even further. A language is a system that embeds a way of thinking about the world (or, if you believe Sapir-Whorf, actually constrains the thought possibilities of the speakers) and constructing a language is a form of world-building that forces you to engage directly with thoughts and philosophies.

In Ancient, the words combined out of primitives hint at a specific way of understanding the world. The word for an Emperor is related to the word for a God, and that word in turn is built out of the concepts of personhood and knowledge. The word for peace means a place that contains no enemies: a negative concept, very different from a peace based on compromise, resolution, or justice.

But a great deal of Ancient is English in a chiffon-sheer disguise, from the word order to the handling of homonyms to the fact that grammar ideas like “first person” are embedded in the language though there is no guarantee that a different grammar system would refer to them this way.

I had a bit of mental friction when “There is a…” — an existential use of “there,” to assert that something is present in the world — was translated with primitive glyphs more suited to the deictic meaning of “there”, the opposite of “here”, pointing out a location not associated with oneself. Yes, in English, we use the same “there” in “there is a dog” and “the dog is over there.”

Not every language does, though. Even languages as (relatively) close as French and Latin handle this very differently. French’s “il y a” would literally mean something like “he has there.” Latin, meanwhile, just piles that extra meaning on “est”, which otherwise means “is”. But Ancient does use “there is”, while spelling the word with glyphs that specifically encode the deictic meaning. I am a weird pedant, but it was a moment when I found it particularly hard to pretend Ancient was something other than an encipherment of English.

But never mind the individual idiosyncrasies. What deeper and more resonant world building might have been possible had the game been able to teach a few stranger ideas in its language? If it contained a few concepts that could not easily be pinned to a single English noun? What if, in a culture with a deep philosophy of cyclical repetition, there were a verb tense specifically dedicated to the concept of did-and-will-again?

More esoteric effects might have been hard to teach, certainly, in a game; and I don’t feel any distress that Heaven’s Vault omitted the linguistic drift, the dialect and spelling variations, the damage to letter surfaces, and the varied writing conventions that make classical epigraphy a specialist field in its own right. (Check out boustrophedon for a good time.) But I do think a few more resonant truths about the minds of the ancients could have been smuggled to player within the form of the language itself.

Procedural Text and the Particularity of History

The world of Heaven’s Vault is crowded with objects, and many of the smaller and less-important ones have what I think must be procedurally generated descriptions — a small bent tablet, a worn copper telescope, a sextant. This works very smoothly, in the sense that I seldom if ever encountered a description that didn’t feel idiomatic. Moreover, there seemed to be a thematic connection between the general type of object and the sort of inscription one might find there, so a navigation-related artifact would likely be inscribed with a message about not getting lost.

For my own aesthetic proc-text preferences, though, the generative grammar was a bit too homogenous and the elements too singular in meaning. A bent metal tablet might be different from a smooth wood tablet, but none of the descriptors were significantly more surprising than others; none of the combinations of description stood out as meaning more than the sum of the parts. It’s the classic bowl of oatmeal problem; or in Parrigues procgen terminology, there is no Venom at all. In a related interview, Jon Ingold makes clear that he saw the dialogue riffing on the generated content in a way that provided the missing variety, and I see his point but also believe more could have been done within the generated material proper.

(As a side note: I saw an excellent talk several years ago about how Pixar animators use a Pareto distribution to distribute a few large objects and a lot of small ones when, e.g., automatically generating a forest. Sadly, I’m not able to find an article about this, or any recordings of the talk, but it made an impression on me because of how natural and pleasing the generated material looked.

Since I haven’t been able to find this talk or any images from it, I will instead illustrate this with a picture of Sprinkletti cake decorations, which similarly come in a large-and-small distribution, though whether accurately Pareto-esque, I am not sure. I mention this because I think a similar principle describes the most effective distribution of unique, unusual, or surprising content vs ordinary and bland content in generated text output.)

Something similar might be said about the actual content of the less-important inscriptions. Inscriptions on big monuments typically had some major narrative function, but inscriptions on pieces of sailcloth were more generic: “follow the wind”, say, or “do not get lost.”

Here I would have dearly loved a little more particularity of content and a little more variety of tone. I am doubtless bringing to bear the Greco-Roman perspective of my own training, but in that context, among inscribed or painted texts you encounter a range of maker’s marks (“Phaedo painted this”), labels (“the guy on this vase painting is Achilles”), personal and sexual graffiti (“Marcus is a thief”, “Anthea has pleasing buttocks”), inventories and calendars (“ten wine skins and two oil jars”, “market day is the fifth of the month”), prayers and votives (“may the person who stole my clothes at the bath die of a plague”, “thanks to Asclepius for healing my infected foot”), records of manumission (“Ignatius purchased his freedom for five gold coins”) and burial inscriptions (“here lies Chloe who died in her twelfth year, before she could be married”).

They are often profane or banal, and at the same time they often hint at very personal stories, and I find them touching. The museum at Ancient Corinth has — or had, when I was there twenty years ago — beautiful sculptures and monumental objects on public display, and then a basement crammed with the cookware, the worn coins, the second-rate vases, the smaller and cheaper statues, the tiny metal figurines and laurel wreaths that were mass produced for poor people to give to the gods when they couldn’t afford something worthier. It was in the basement that one felt the crowded humanity of history.

There were one or two items in Heaven’s Vault that came close to doing that for me: a gift given with an instruction to remember and come back to the mother who gave it, for instance. And perhaps the authors felt that the vocabulary to cover market days, bath thefts, infections, and shapely posteriors would have been a distraction from the story they wanted to tell. But I longed for the added texture.

Game Feel for Choice-Heavy Games

I said at the top that this is a game about piecing together meaning from small bits, and that’s true at the narrative structure level also. The plot comes in atom-sized pieces which may be distributed as necessary. There are many moons to visit, and various incidents that can happen on these moons, but they can occur in almost any order; you unlock access to new moons by finding a sufficient number of artifacts that come from the source world.

Not only that, but the choices you make when translating inscriptions feed into the dialogue you have with other characters, so that your guesses about the meaning of text ripple outward into personal interactions.

In consequence, there’s a lot of potential variation in what happens, in what order. In some places that’s evident, but in most places I know about it only because I’ve heard from other people about the alternate experiences they had in play. At the same time, few of those choices are framed as high stakes. Meanwhile, the explicitly high-stakes choices you are allowed to make (whether to hand over an important artifact to someone you no longer trust, for instance) sometimes have disconcertingly minimal consequences.

So, at least in my own experience of the game, the choices that were framed as meaningful tended to do less than I expected, while actions with no signaled importance turned out to shape the later flow of the narrative.

The result is a very rare thing: an interactive story in which the player experiences much less diegetic agency than she actually has. The world is full of interactive stories that use smoke and mirrors to convince you that you’ve made a difference. Heaven’s Vault frequently deceives you into thinking that you haven’t. Though your actions massively reshape the story, most of the time it feels like you’re being swept along one of the Nebula’s rivers, able to make only minor adjustments to your course and speed, uncertain about where these tweaks will take you.

I’ve recently been reading Steve Swink’s book Game Feel. I have been doing this because although Swink describes game feel in a way that is very very explicitly not about narrative text games, the description resonates for me with a sensation of agency and narrative control that I believe many narrative games attempt and few achieve. Here’s how Swink defines game feel:

Real-time control of virtual objects in a simulated space, with interactions emphasized by polish.

And he talks about fighting games and driving games; this is not about interactive stories. But a bit later, he writes

The aesthetic sensation of control is the starting experience of game feel. It is the pure, aesthetic pleasure of steering something around and feeling it respond to input.

And isn’t there, sometimes, a pure aesthetic pleasure of steering a narrative? A rare but eminently desirable experience when, for instance, we know that the protagonist is on the verge of doing something very stupid, and we tiptoe up to the edge of disaster before withdrawing; when we know that a particular statement will send an NPC over the edge into a dramatic rage, and we choose to say the words? This is something I tried to explain in my talk at Progression Mechanics a few years ago, though I had not at the time read Swink’s book.

I can pick out dozens of specific beats in my own work where I was trying, whether or not successfully, to create this feel for the player: in Alabaster, when the player is driving Snow White to the breaking point with a particular line of questioning, and the imagery in the sidebar becomes more and more aggressive to indicate that we’re close to disaster; in Glass, when as a parrot you can wait out an NPC-driven conversation to drop exactly the right word into conversation at exactly the right time, and cause havoc; multiple times in Blood & Laurels where there are opportunities to flatter or offend strategically. And I’ve found it in other works also: the most famous puzzle in Spider and Web, a late game moment in Portal 2; the alternate endings of Slouching Towards Bedlam; quite a lot of Ingold’s own Make It Good, once you’ve played the game through eight times or so and are beginning to get a notion of what you’re supposed to do.

A single large choice rarely accomplishes the effect, for me, unless it’s been set up as the consequence of a long quest — which is why I am interested in microstructures of choice. Those small “are you sure” moments that set the stakes or provide a bit of additional stake-setting give those choices just enough heft, enough weight, to make steering feel good.

But in Heaven’s Vault, those microstructures are sometimes deployed to ask whether you’re sure about an action that will actually have no consequences to speak of, while other actions are too light, without even a “Six will remember that” to warn you that they mattered.

A Cold Heaven

Ultimately, Heaven’s Vault left me with a strong sense of isolation and loneliness. Even the protagonist’s own backstory is presented as a series of dates on her timeline, there for you to explore if you want. I found that both extremely clever, and expressive of Aliya’s essential disconnected quality.

Other players have complained that her dialogue is not what they would choose to say themselves. I generally like a highly characterized protagonist, but I found Aliya’s character uncomfortable to inhabit. Perhaps this too was the result of some inadvertent stat-setting I unknowingly did at the beginning. But my Aliya soon revealed herself, against my will, as a scientist who was nonetheless strangely incurious about Six’s past and memories; a nominal abolitionist who abused her robots even when it became clear that they had some level of personality and sentience; a figure who resents being used but is highly utilitarian in her approach to others. Is there ever a moment of open connection between her and anyone she meets?

At one of the crowning moments of the story, Six retrieved an entire codex for me, a huge book full of ancient and revealing inscriptions to read. As a player, I coveted it more than anything else in the game. As a character, Aliya seemed to feel the same. But even then, there was no “thank you” in the menu, no opportunity to show Six a little appreciation.

At the end of the game, I made a destructive, antisocial decision, and I did so for two reasons:

- I didn’t really care about the people I was leaving behind me, and Aliya definitely didn’t care about them

- I was eager, finally, to pull a lever and see a significant result

After the times I’d tried to do something big earlier in the story, this felt like my last chance; as though if I didn’t take action, the Nebula would continue in a depressingly static state.

And now I’ve gone on at horrible length about all this: this is an astonishing game. I really want more people to make more conlang narrative games ASAP, and I am also extremely impressed by the flexibility of content that inkle managed to create.

Other reviews and coverage:

- Andrew Reinhard at Archaeogaming, on the archaeological aspects of the game

- Katherine Cross at Polygon, on how replaying captures the game’s own “loop” concept

- Alice Bell at Rock Paper Shotgun, enthusiastically

- Jessica Famularo interviewing inkle about the language design for Gamasutra

and if you found this interesting, you might also enjoy the language-focused tabletop RPG work of Thorny Games.

(Disclosure: I played a copy of this game that I purchased with my own money, for the PS4.)

It sounds like the kind of game I didn’t know I was waiting to play. Hopefully there will be a Mac port at some point.

Your remarks about the possibilities of using the language to present ideas and perspectives that don’t map 1:1 onto English reminded me of this passage in Stranger in a Strange Land:

‘ “It is later than you think” could not be expressed in Martian—nor could “Haste makes waste,” though for a different reason: the first notion was inconceivable while the latter was an unexpressed Martian basic, as unnecessary as telling a fish to bathe. But “As it was in the Beginning, is now and ever shall be” was so Martian in mood that it could be translated more easily than “two plus two makes four”—which was not a truism on Mars.’

Isn’t the lack of signposting on significant choices a conscious part of Jon’s design philosophy? In _Adventures in Text_, he talked about how he goes to some lengths to hide how player agency works in order to make it difficult for players to game the system. So he says that he always likes to have the game completely ignore the obvious thing about how your choices turn out, making consequences depend on results that you are unlikely to anticipate on a first playthrough. And in 80 Days I gather that the game deliberately provides different journey options on consecutive playthroughs so that it’s impossible to go right back to the same situation and try playing it differently.

I don’t think “make it hard to game the system” has to mean “allow for no intentionality” or “give no perceivable consequences after the player does something that was signposted as a Really Big Deal.”

Like: you can have the game acknowledge what the player was trying to do, and then respond with “okay, nice try, but your plan backfired in the following way…” That’s good plotting: we get complications arising from the player’s intervention. (Elsinore is loaded with complications of this kind, though that’s a bit of digression — just on my mind because I’ve been playing it.) Or you can bring back consequences of things that the player thought were trivial. Those are both, in my opinion, reasonable tricks.

It’s more head-scratching to set something up as an action that will necessarily have major consequences to the storyline and the major relationships with other characters, but then have characters respond to it with “…huh well that’s interesting, uh, go do some more exploring and I guess we’ll chat more later.”

Ok, let’s do this.

You and other critics have pointed about that the traveling sections are a kind of a low compared with the rest of the game.

I have an idea for a project that is an epic ecological tale about a whale looking for answers and retribution about the bad behavior of humans against the oceans. The main concept is “Visual Novel about whales”, that’s the gist of it, but the concept is growing little by little in my head, with scenes like a conclave of whales, gaining the trust of organized groups inside the animal life in the oceans (each in each own territory), visiting a whales graveyard for the proper rip off of The Ancient Morla, that is called The Ancient Cetacean, etc.

So, Visual Novels are usually just about conversation, conversation, and good portraits, but I’m having problems imagining how to fill the game with mechanics of exploration between dialogues and dialogues. Should I have a 3D exploration game with a 3D whale? Should I have a beautiful rendered 2D exploration marine environments? Should I have just a minimalistic worldwide map to show where the whale protagonist is going?

So, as you mention in the review, voyages in other media are non-exhaustive affairs (I’m citing from memory), so, why games just handle traveling so bad, and so literal?

Even in novellas about the village, or films, the act of traveling is highly structured and edited to show proper storytelling, even so, the film or narration of the stages of the voyage are suspiciously related to dialogue and relations between characters (think of the second half of Neverending Story).

So, lately, I’m thinking about using 2D environments, but with short treck of distance to cover, highly related to drama, that be, conversation or for mood and ambiance. Of course, just copying of cinema and literature.

Tangentially related, I tried some of this approach in my last game from 2017, Tuuli. In that short piece, I even shortened making narrative jumps, and ellipsis, putting the player in the proper place to keep the narrative flow coming. In the end, I failed to do this exhaustively, because when the chief commands to go to the top of the cliff, I just obliged the player to reach it as we play normally adventures. But that is because, in the end, I decided that the process of the seeking of the objects needed to perform the ritual was narratively important too than to just to teleport the protagonist to the cliff with the ceremonial dagger already in the inventory.

I mean, some of our interactive fictions and adventures are about traveling around an empty place. So I understand the need of sharp our narratives using advanced narrative techniques and such, but sometimes, as Veeder put it in the Bronze podcast, the “go-to” command betrays the thematical pleasure of traversing and learning the way around the castle.

So… in the end, I just don’t know what to do with my epic about whales :)

Anyway, it would be nice to see more interactive fiction exploring traveling more elegantly than just exhaustively trodding of the land.

Errata: I meant “novellas about voyages” not villages.

As always, this isn’t a one-size-fits-all situation. Times when I think mimetic travel is effective include:

– when a major aspect of the gameplay is about exploring a space (true for a lot of classic parser IF, and also for the sorts of games typically called walking simulators), especially when there’s a fair density of new content in the locations you’re visiting; also, where something about inhabiting a 3D space actually allows you to experience the places in a new way (e.g. the way several of the Myst games provided a wondrous environment constantly yielding new vistas… and even there, there was a fast-travel option)

– when something else significant and engaging is happening during the travel, and that’s really the focus, so that the travel element is more about providing changing scenery (Railways of Love, the conversation scenes while you’re on the back of an elephant in The Meteor, the Stone, and a Long Glass of Sherbet)

– when the travel progress is actually working as a kind of timer or countdown for the other activity you’re doing — this is kind of a higher-pressure variation of the above; for instance, To Hell in a Hamper

– when spending the time to take the journey itself has an emotional effect: I’m thinking of the slow travel in some of Tale of Tales’ games, The Path especially; or the final walk in Firewatch. In The Path, it’s still quite annoying to have to do, but that annoyance is deeply connected with the nature of the game experience you’re intended to have

Places where I think it works less well:

– where none of the verbs/actions of journeying have any narrative or gameplay meaning to speak of, so you’re just killing time

– when the same journeys are repeated over and over with no new content or meaning

– when the journey lasts longer than whatever emotive content its offering (so a common thing is for a game to have some travel animation or music that is cool and enjoyable for the first time or two but then becomes dull long before the player is done traveling)

Oh, and bonus resource. Strictly this is about time rather than about space, but this old IF discussion club transcript involves people discussing how to handle jumps, cuts, etc.: https://emshort.blog/how-to-play/if-discussion-club/transcript-of-april-5-2014-ifmud-discussion-on-time-simulation/

Nice info, thanks!

It is amazing how different Heaven’s Vault can be perceived. I am one of those players with NG+7 who gather and compile complex timelines and sample collections involving a description of origins, date and locations that have involved in finding the inscription. HV is one of the most META games I ever played, as it allows deducing so many things from actually playing and observing the game outside of the mechanic. Yes, I have a handwritten Ancient Dictionary with sketches of the locations and notes about the spoken Ancient in the game. And I don’t feel the least odd about it. This META level actually added a very interesting layer to a game that went missing from other games for a long time. Maybe you remember games that made you draw your own map? This takes drawing your own map on a new level.

You mentioned a certain lack of stratigraphy, but during NG+3 or 4 you start to notice how the layers of the cloud’s history pile onto each other. How, if you take the actual “historical layer” into account, the meaning of what has been said will change. You might notice how a difference in the kind of fonts and script actually give little hints on the period and what kind of person or machine fabricated that text in which context. Suddenly you notice that what you may find might actually be as interesting as what was written on it. It allows conclusions on the actual period, on how to evaluate the position of humans and machines over the centuries, and question your first deduction about what actually happened in the past. As you wrote it, the actions change the story. But in the case of Heaven’s Vault it changes how our character actually sees history (in this playthrough). It is up to us to actually decide what really happened as we can loop around.