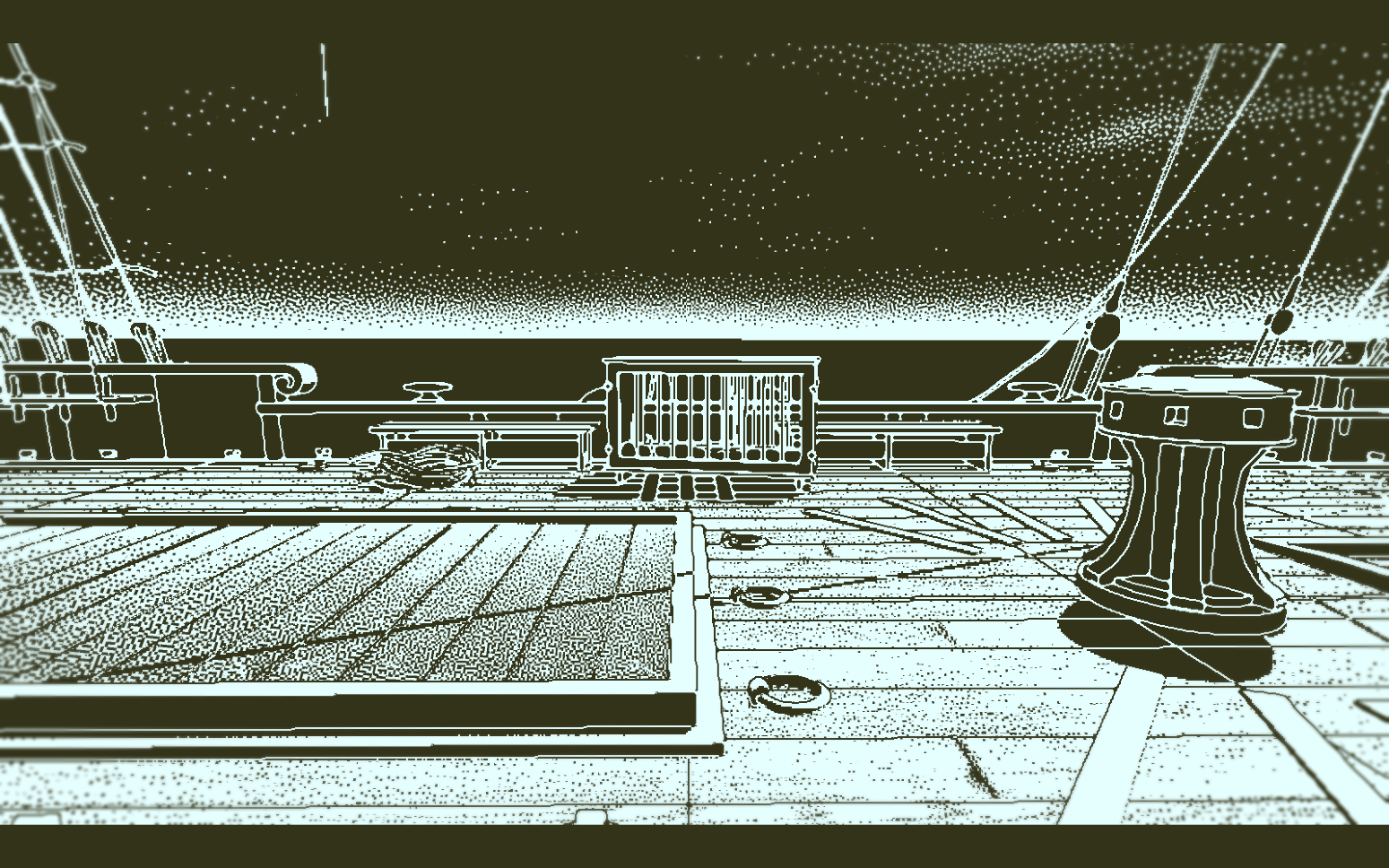

Neo Cab tells the story of Lina, a gig economy driver about ten years in our future and in a slightly-alternate reality. In that world, a company called Capra — part Uber, part Tesla — has rolled out a fleet of self-driving cars that make human drivers largely obsolete. Lina can just about make ends meet, barely, but she’s been invited to Los Ojos to live with her old friend Savy, and that seems like a very welcome life change.

Surprise surprise, though: when she gets there, Savy’s situation is not quite as straightforward as she’d hoped.

The story plays out passenger by passenger: the loop consists of deciding what passenger to pick up next, having a conversation with them in the car, and dropping them off. There’s some light gameplay around trying to keep your passengers happy enough that your driver star rating remains above 4, and not spending so much money that you can’t afford to recharge your car or get a bed for yourself at night.

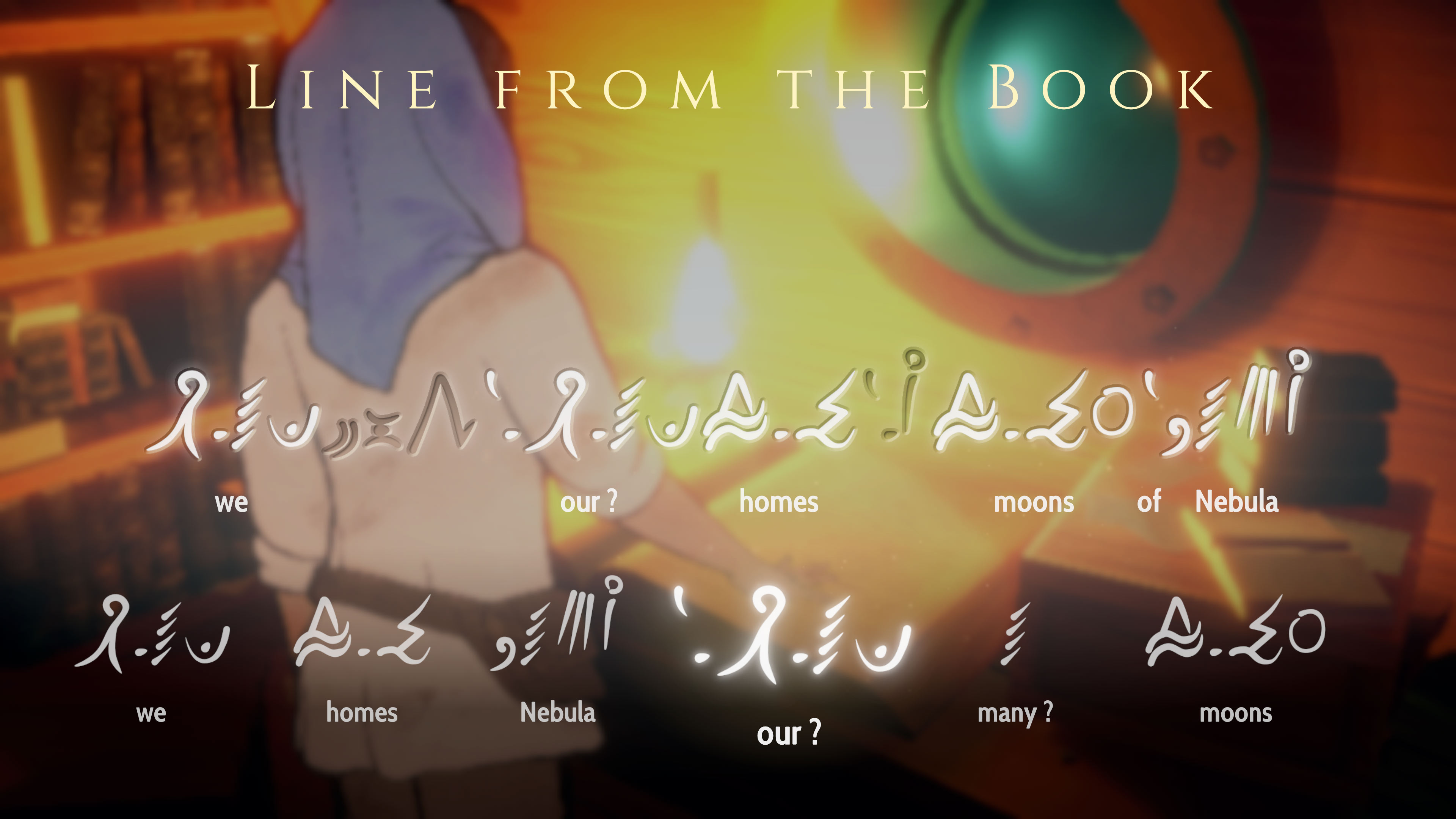

But mostly, the substance of the game is conversation, very lightly animated. The things you’re allowed to say depend partly on the mood you’re in, with conversation options tinted different colors if they happen to be unlocked by your current frame of mind:

…and on the rare occasions when you’re not talking to a passenger in your car, then you’re probably talking to someone by chat.

It’s not always obvious how your conversation choices are going to drive your mood, and occasionally my passengers reacted to me with less than a 5-star rating when I thought I’d treated them just fine. But the system is forgiving enough that I didn’t find that aspect too frustrating; it felt more like it was representing the reality of a gig economy situation, namely that you don’t always know or control exactly how someone is going to respond to you, and there’s a little bit of arbitrariness in the experience.

Continue reading “Neo Cab (Chance Agency)”