Mask of the Rose is a dating-and-murder-mystery virtual novel set in Failbetter’s Fallen London universe. In line with that genre, it typically gives the player between two and four dialogue choices for conversation – occasionally more or fewer than that, but usually keeping things in that range.

The trick was, though, that we wanted to actually grant the player a lot more latitude than that to decide what they wanted to say. I’ve always been interested in expressiveness in player dialogue, both as an aid to roleplaying and as a way to enable intentional, high-agency game play.

My goal in designing this way is to let the player plan ahead, adopt specific approaches to other characters, and play them out, as opposed to being entirely reactive to whatever dialogue choices happen to pop up in a given scene.

In Mask, this takes two major forms. One is through the player’s character traits and wardrobe: at the start of play, you can decide what sorts of conversation options are on brand for you. Do you tend towards jokes or melancholy observations? Are you rigorous about the truth, or do you lie sometimes?

Many games put those personality-characterising options side by side in a dialogue menu, but that means that if you’re trying to play a consistently melancholy character, you’re stuck with your dialogue choices pretty much pre-decided for you: you just have to pick the one Melancholy option every time. And there isn’t really as much room to define your PC around multiple distinct types of trait, whereas in Mask we wanted the player to be able to combine, e.g., being melancholy and boastful, or gloomy but confiding.

To accomplish that in Mask, we have a larger pool of potential dialogue at any given stage in the conversation, and filter it to show just the options that are currently suitable for the player.

(If you’re interested in the technical aspects of doing something like this in the Ink language, by the way, I recommend Inkle’s posts on Overboard!, where they’re also drawing dialogue options from a pool each turn.)

Of course, our choices can be determined by situation as well as by personality, so for Mask we let the player further inflect how they’ll present themselves using the wardrobe. Different wardrobe items advertise different social affiliations, or spin the PC towards a snobbish, flirty, or unfriendly self-presentation.

That got us halfway to where we wanted to go, giving the player range to roleplay someone with a specific social style, using a fairly large palette of available options.

Beyond the social element, though, we also wanted to deal with knowledge, and let the player express particular ideas or ask particular questions. Handling player knowledge is always a significant challenge in interactive narrative: while you can track what the player has seen during gameplay, you can’t track what they remember, and you definitely don’t know what they’ve concluded on their own. So if the aim is to present the player with the ability to articulate the state of the world as they actually understand it, you first have to find out what the player does understand. Which isn’t always easy.

Many mystery games just dodge this problem completely and use straight adventure game mechanics (solve this string of puzzles and you’ll find the necessary evidence). These might be using other genre trappings of a mystery, but they’re not really asking the player to deduce the solution. Other mystery games ask the player to demonstrate they understand the mystery’s logic, but still only in reactive circumstances, like presenting counter-evidence when a witness lies in Phoenix Wright, or noting when an NPC has said inconsistent things in Contradiction.

For Mask, we wanted to enable an active process – one where the player forms hypotheses, investigates their ideas, and refines what they think based on new information.

To let the player express their hypotheses, we put together an interface where the player has a sort of red strings murder board (without the actual red strings). This is essentially a crafting system, and one in which the player can craft both questions about the mystery and their own finished explanations for what really happened.

Once they’ve formed a hypothesis, it opens up options in dialogue… though it may still not always be wise to say what’s on your mind:

The storycrafting system is best shown off with some screenshots. These shots are not completely spoilery, but if you want to play Mask of the Rose fresh, you may want to stop here. (And in that case, you may like to know the game is currently on sale on Steam.)

For those open to mild spoilers, here’s a bit more detail. The screenshots and description talk about the very latest release of Mask, iterating on player feedback on some things they found confusing at launch – so if you’ve played and these look a little different, that’ll be why.

Onward:

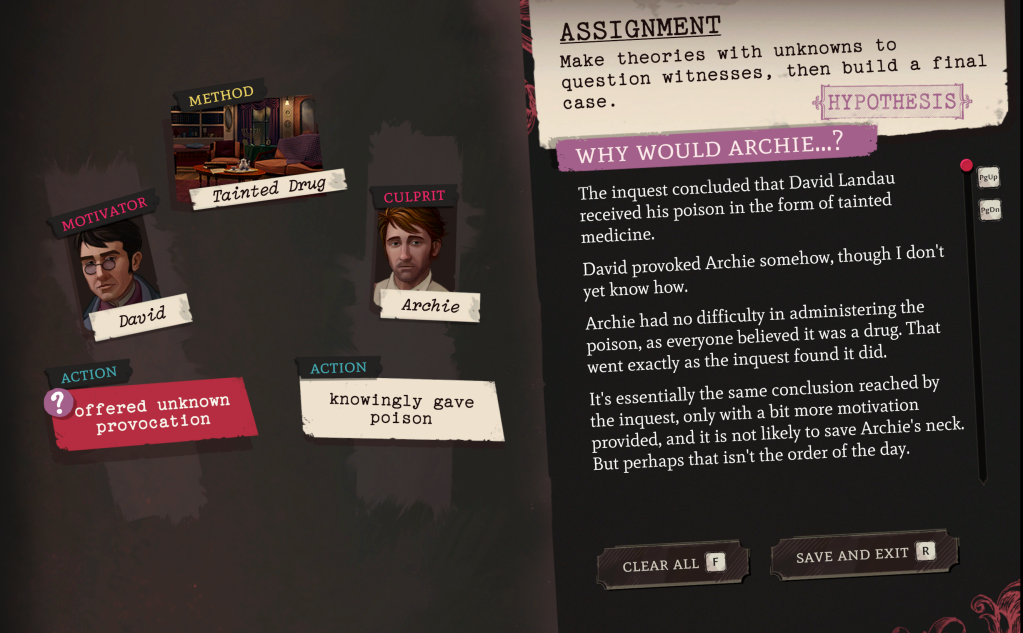

When you’re working with your murderboard, you can put in your own theories about means, motive, and opportunity, based on your inventory of evidence.

Sometimes (especially early on), you won’t yet know enough to be able to plug in a definite answer to a particular spot. In that case, you can use an “unknown” token instead – indicating that you think something happened, of a particular kind, but you don’t know what that something is.

Here we’re expressing the idea that the victim did something to annoy the hypothetical murderer, but we don’t know what that might be:

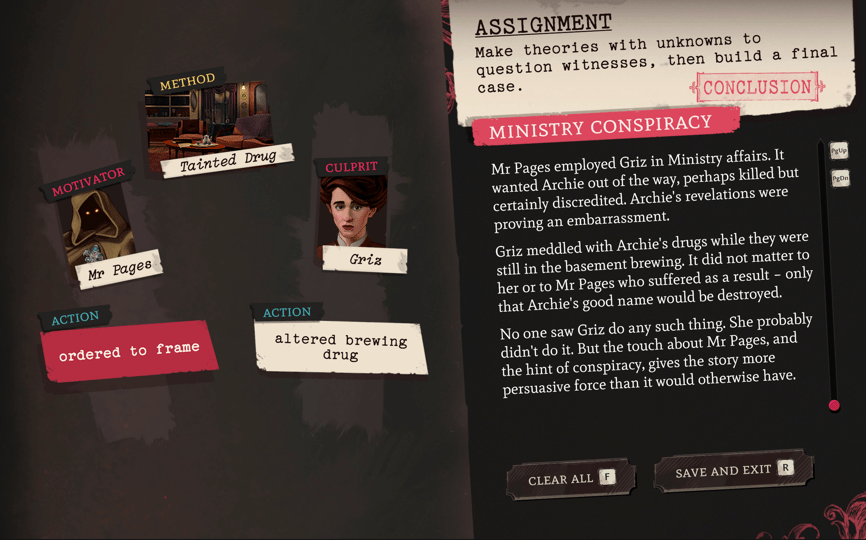

Once that murderboard has been completed, it looks like this:

…which is to say, a finished hypothesis that Archie was the murderer but was reacting to something David did. The text on the right hand side of the screen turns that combination of tokens into a continuous narrative, so that the player can see what the system is doing with the player’s input: we put that together using a tagged expansion grammar.

Going out in the world with this hypothesis then unlocks dialogue to ask different characters about Archie’s potential motivation.

The other thing the system does is check some constraints on the juxtaposition of different tokens. There are some murder ideas that just don’t make sense at all: particular characters who wouldn’t have had the opportunity to use particular murder methods. Because the system is backed by a constraint system, we can prevent the player from constructing those totally impossible theories, and guide them back towards ones that are at least theoretically conceivable.

In essence, this is addressing a challenge that arises with parser-based text adventures as well: if we give the player a lot of freedom to combine tokens of meaning, how do we respond when they put them together wrong? And how do we steer them towards combinations that do make sense?

Using the murderboard and the inventory of discovered evidence, we let the player form and articulate hundreds of different theories, and open up new narrative space every time they have a conversation that presents new evidence. At the same time, by ruling out particular item combinations, we eliminate much of the need to have the game issue the equivalent of error messages (e.g., NPCs complaining that your idea is incomprehensible).

Ultimately, the player can build a substantial range of finished theories, including the truth or partial versions thereof, but also a number of alternative explanations.

All of these can be presented to the court for trial, with very significant consequences for the outcome of the game.

We enjoyed working with the murderboard so much that we let the player do a few other things with the same system as well… but I’ll leave that for another post.

A quick afterward about mystery structures in interactive form: Several of Jon Ingold’s games, including both Make It Good and Overboard!, solve the player knowledge issue by presenting a puzzle situation that the player can only resolve if they’ve correctly analysed the motives and past actions of the NPCs.

I really enjoy this and find it ingenious, but I think it can risk encouraging an instrumental approach to the NPCs: they become pawns on the player’s chessboard, potentially, rather than personas who deserve consideration in their own right. Because Mask is fundamentally a game about relationships, we wanted to go a different direction – and that required structuring the knowledge question in a very different way.

One mark of your mastery is that many of the methods you use (1) are things I never would have thought to do and (2) seem so obviously right in retrospect that I can’t believe they’re not already the accepted way of doing it.

I love this concept. I’m also really interested in encouraging the player (and NPCs) to plan ahead. I did something vaguely akin to this in a prototype I made for my dissertation (http://cs.uky.edu/~sgware/projects/blp/). You act out how you want to complete a quest and then you watch it happen, with my system throwing in conflicts to make it go wrong. Then after it went wrong you would start acting out a new solution right before it went wrong, and it would go wrong in a different way, etc.

It isn’t actually fun to play… in fact it’s quite tedious, partly due to the lack of polish, but also because it’s just annoying. We implemented the game this way precisely because of the challenge you highlighted of trying to predict what the player is planning. We “solved” this problem by just making them tell us exactly what they were planning. Your murderboard seems like a solution which is both more elegant and less tedious to play with. I love how you can specify partial solutions. This is both a convenience to the player and a source of information to the author about what the player wants to explore. Brilliant.

This game is about reconstructing events from the past which are (presumably?) fixed but unknown. I wonder whether this or something similar could encourage players to plan their approach to a current narrative situation. That’s also unknown, since it hasn’t happened yet, but in a different way that might be interesting.

Re. “To accomplish that in Mask, we have a larger pool of potential dialogue at any given stage in the conversation, and filter it to show just the options that are currently suitable for the player”:

I haven’t played the game yet, but this feels to me like forcing the player to roleplay–which means they aren’t really roleplaying at all. Roleplay necessarily means choosing to act in-character. If they can’t choose, it isn’t roleplay.

I realize there’s value in assigning “character classes” to assign a backstory, or at least a social class. But I’m not convinced that all roleplaying stories should use the Dungeons-and-Dragons roleplaying training-wheels of character classes. Imagine, instead, a character creation method in which the player assigns not just points to stats, but points and cash to stats and props. Think of each player as trying to “pass” as their role. Someone who wants to be called Professor had better have a tweed suit. Someone acting out-of-character for their profession, gender, or even race might get called out on it, depending on the setting. Someone trying to intimidate who hasn’t got the stats to back it up, or wears foppish clothes, or has folded to previous threats, will get hurt. And so on. Then you can give everyone all the options, but they’ll have problems if they try to multi-class too much. Roleplaying would then become an actual in-game skill that must be learned.

I understand what you’re describing, and I can imagine that being fun for some players. (Honestly, I’d probably find it fun myself, in the right circumstances.) But I thought the desires of our own player base looked more like this:

– I don’t want to solve puzzles in order to be allowed to present myself as I wish in the game world

– I don’t want to have to choose between saying something that feels in-character but doesn’t represent my current goals for this scene (right HOW to act, wrong WHAT to do), and something out-of-character but aligned with those goals (right WHAT, wrong HOW)

– I do want the game to present me with multiple dialogue options that all feel like things my character would say

– I do want new choices to feel at least somewhat fresh per situation and not like I’m making the same very basic characterization choice over and over again

as well as

– I don’t want to be overwhelmed by having to read through and think about 12+ dialogue choices at each point in the game

So that required some filtering, and an ability to take their initial input on characterization in order to then offer them a palette of additional options that would feel consistently relevant.

Heavens, Emily, I was concerned- you usually have written frequent updates and recaps of newly-released games and tools. You must be extremely busy, which is a good thing! Admittedly, though, I miss all of the condensed knowledge you put out on the regular. I hope your next project is going well.

Thanks for the kind words. It’s a mix of “busy” with “shifted priorities.” I’m glad people have valued the blog in the past and continue to use it as a resource, and I have no intention of taking it down. There was a period when I took an intentional hiatus from posting, for various reasons. That’s now over, but I find new posts attract fewer readers than they used to, now that I am no longer on Twitter and no longer tweeting about each new post.

So while I have various post topics I’ve kicked around in recent months – and I’ve given a few talks this year that could be linked or recapitulated here in some form – I’m ambivalent about the value of picking up a regular posting practice again without also having a bit more of a plan for publicising the results.

(To address a couple of the more obvious suggestions on this front that I’ve already considered: I really don’t want to rejoin the platform that is now X, and I’ve generally found that engaging less with social media has been a positive thing for my sanity lately. A few people have suggested moving to other blog or mailing list platforms, but it’s very unclear to me that I’d gain more than I lost by a change of venue, and there’s so much old content on this site that I’m definitely not going to try to move it all.)

Hey, your blog was kind of important to me, I hope you’ll be coming back to post at least from time to time. Best luck to you!