Judy Malloy’s The Yellow Bowl is a very early hypertext, originally written in BASIC in 1992, and then a few years ago converted to be accessible on the modern web. In her introduction to the new version, she writes

Welcome to the transmediation — from BASIC to JavaScript in an HTML/CSS environment — of The Yellow Bowl. Originally containing approximately 800 lexias, The Yellow Bowl was first presented at “Hypertext, Hypermedia: Defining a Fictional Form”, a 1992 MLA panel, chaired by Terry Harpold, where I said:

“In my narrabase, The Yellow Bowl, the contrast between the narrator’s ‘true’ memories and the ways she distorts them to shape the story places the reader on the uneasy ground between the narrator and the narrative.”

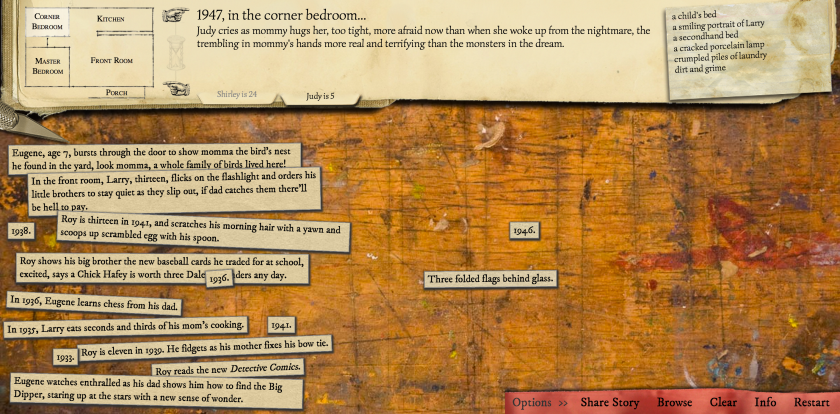

The piece features three narratives: a main storyline about the protagonist Grace, filling the center of the screen, and then two adjacent narratives, which are speculative fiction/fantasy stories that she is making up about two different women who are trying to escape oppressive environments. All three narratives contain a fair amount of domestic detail, of the preparation of meals and the mundane texture of daily life. In the end, the side narratives will end with the two fictional characters meeting.

The reader may advance any of these three narratives at any time, changing which lexia sit next to which; there’s some basic text animation applied to the left and right text streams, so that they flow into place rather than just appearing. There are also a few clips of sound, passages from the text read aloud.

All of these elements feel very much of 1992 — not because it is unfathomable to have animated text effects now, and indeed inkle have been very eloquent about the value of this kind of technique — but because the implementation emphasizes the computer-nature of the text as though that were a novelty, while doing nothing to ease the human process of reading it. The letters dance up the screen, making you lose your place if you try to read before they have finally settled.

Reading this text, I immediately feel a kind of discomfort I’ve come to recognize. When text is presented to me this densely on a page, and there are this many affordances for things to do, it makes me anxious that I will not be able to read it thoroughly.

Even a printed book can have this effect on me, if there are too many sidebars, and especially the parallel texts run together longer than a page or two. S. caused a bit of it, until I came up with a strategy. Curiously, I usually don’t have this same issue with densely-footnoted books, because the footnote enumerations do suggest a clear reading strategy and promise me a way back into the main text when I am done.

In considering ways to read this work, I found myself considering other juxtaposed or parallel-track pieces I might have encountered before.

Before we even reach digital hypertext, there is the Oulipian A Hundred Thousand Billion Poems of Raymond Queneau, in which lines of poetry may be freely remixed: choose any of the first lines, followed by any of the second lines, and so on. However, the formal structure of a fourteen-line poem provides a certain consistency to the experience, and keeps it from being too bewildering.

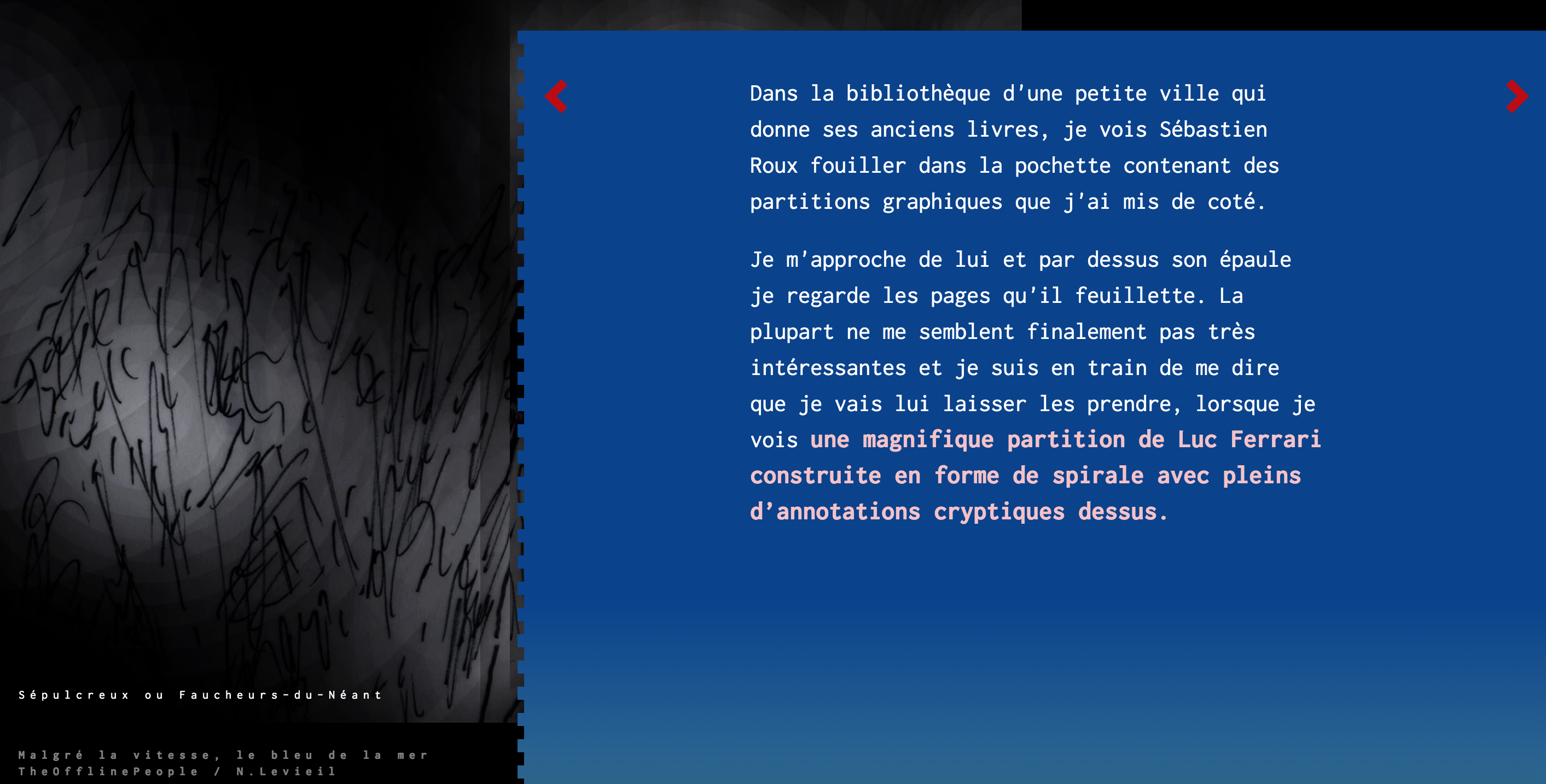

A much more recent work, again working with free juxtaposition from fixed corpora, is Malgré la vitesse, credited to TheOfflinePeople / N.Levieil. In this piece the reader may choose either an image or a passage of text to be uppermost. There is a track of images and a track of texts; you may advance either, thus remixing what image appears next to what text. In contrast with The Yellow Bowl, Malgré la vitesse allows us to travel backwards as well as forwards, perhaps to search for a more suitable combination.

I am somewhat constrained in my ability to critique this piece because my French is only good enough to give me a sense of what is going on, but not literary enough to permit me to draw any observations about the style.

These are almost the only two works of this format I can readily think of. The other closest formal examples might perhaps be The Reprover, in which juxtaposition of image and text take a role, or Harmonia, in which the core text is provided and the player then chooses to click to open up marginal notes. But in neither case are the elements of the text really on parallel tracks.

In Arcadia, meanwhile, the reader has a map that shows which events are happening simultaneously (to the extent that’s meaningful), but we’re never tasked with more than one column on the page at a time.

Then there are the games, both parser and Twine, that split screen present simultaneous viewpoints of the same event from two perspectives. Rosencrantz’s Silver and Gold presents a sort of chase this way:

Narcolepsy, one of Adam Cadre’s parser games, also uses facing pages this way, with the right page tracking the reader’s thoughts:

But in all of these cases, the relationship between the left and right text is fixed to some underlying world state, and it is that state which the player is concerned with altering or affecting.

In Malgré la vitesse, by contrast, our manipulation of text and image don’t change what is happening in any way (at least, not as far as I could tell); but the point is to allow the reader to combine pairings that were of some conceptual value, a streamlined version perhaps of the central mechanic of 18 Cadence.

The Yellow Bowl, however, doesn’t closely correspond to any of those examples. It is more narrative than Queneau’s poems, more complicated in structure than Malgré la vitesse, and less purely juxtapositional than 18 Cadence. Its parallel tracks are neither entirely coupled nor entirely separate. At some points in the narrative, one of the side tracks will offer an opportunity to change what is in the main track, as here, where the sideways-pointing arrow at the bottom of the right-hand column will refresh the middle column instead.

Because the middle column represents the mind of the protagonist-narrator Grace and the right column represents events happening to her character, this suggests that Grace’s flow of thought has been altered by the events affecting the side character.

At times it seemed to me that clicking these links, I was fishing up from the depths the backstory in Grace’s real life that had given rise to a particular narrated event or image.

At other times, it felt like the consequences were random, or arose instead from the chance arrangement of two elements.

The Yellow Bowl refers to itself several times as polyphonic, which might refer to the three protagonists, but also to the sound files in a single recorded voice layers with itself many times.

Over and over I found myself looking at more of the author’s website, prefatory notes, map text, and other extradiegetic material. The more of the surrounding text I took in, the more I found myself able to read The Yellow Bowl comfortably. It is hard to use the text to find out what is happening, or why, or how the elements relate to one another. It is much easier to approach the work having already understood what the different areas of text signify, and even that the two side characters are moving steadily toward each other; and then to read in a way that lays in colorful details like mosaic stones on this existing armature.

At breakfast, women sat together around a long table. The meal was oatmeal wth cinamon sugar, pecans, and raisons, homemade scones with butter and jam, apple cider, and tea.

One of Helen’s paragraphs; one of many that enumerate all the foods in a meal. (The spelling is as copied here.)

Many of the side paragraphs of The Yellow Bowl — the descriptions of meals, of the shapes of hedges and the colors of carpets, of the shape of a shell — have nothing to say about plot, but everything to say about how and why the stories are imagined. They are one Proustian madeleine after another.

Meanwhile in the main narrative contains some contextualizing events, some of these same sorts of descriptions, and then also a great number of references to reading matter and ways of reading:

I took The Scarlet Letter from my backpack and began to read. I had lost my place, a circumstance that occurred regularly with this book to the extent that I was never able to read it in one sequential stream and was always beginning again with the Customs House.

One of Grace’s passages in The Yellow Bowl

…since, The Yellow Bowl seems to say, the reading matter is fodder for the writing.

The Yellow Bowl also reflects the time in computing to which it belongs. It is still surprising, in this universe, that you might get to know someone online, that you might form a long-distance friendship via text. A few passages suggest contemporary MUDs:

“The Living Room

Part of Helen’s story

It is very bright, open, and airy here, with large plate-glass windows looking southward over the pool to the gardens beyond. On the north wall, there is a rough stonework fireplace. The east and west walls are almost completely covered with large, well-stocked bookcases. An exit in the northwest corner leads to the kitchen and, in a more northerly direction, to the entrance hall. The door into the coat closet is at the north end of the east wall, and at the south end is a sliding glass door leading out onto a wooden deck. There are two sets of couches, one clustered around the fireplace and one with a view out the windows. You see Clara.”

Several of the 1990s literary hypertexts I’ve tried, I’ve found challenging because they seemed quite foggy; ideas and themes surfacing from the text and then subsiding again; no definite or purposeful shape evident in the traversal. Depending on whom you ask, that is either the best or worst thing about hypertext at the time. Take Robert Coover, writing also in 1992:

And what of narrative flow? There is still movement, but in hyperspace’s dimensionless infinity, it is more like endless expansion; it runs the risk of being so distended and slackly driven as to lose its centripetal force, to give way to a kind of static low-charged lyricism—that dreamy gravityless lost-in-space feeling of the early sci-fi films. How does one resolve the conflict between the reader’s desire for coherence and closure and the text’s desire for continuance, its fear of death? Indeed, what is closure in such an environment? If everything is middle, how do you know when you are done, either as reader or writer? If the author is free to take a story anywhere at any time and in as many directions as she or he wishes, does that not become an obligation to do so?

“The End of Books,” Robert Coover, The New York Times Book Review 11, 23-15, 21 June 1992; reprinted in the New Media Reader

It is in exactly this respect that more modern hypertext out of the Twine tradition tends to feel more accessible and more satisfying to me as a reader; as I’ve written elsewhere, even when there is no story per se, there does tend to be a beginning and an end.

I did encounter some of that “dreamy gravityless” feeling in The Yellow Bowl, especially when after a while the passages about Grace began to repeat randomly; and I think, at the point where I stopped reading, that I probably have missed reading a fair number of lexia. I also felt always at least a little distanced from the two side narratives, perhaps because the framing discouraged becoming too immersed in either for long, perhaps because the worldbuilding felt at times intentionally generic, with locations named Thecity.

At the same time, the two side narratives are running from a beginning to an end — in fact, to the same end — and this provides a kind of guide to the whole piece which I have not always found elsewhere.

Meanwhile, I felt The Yellow Bowl got at something about the simultaneous tracks of a mental life, and about how our memories and ideas, fictions and physical realities all ping off one another; about how the past and the present, the read and the imagined, can coexist in our minds in an exceptionally vivid way, and indeed be in dialogue with each other and influence our actions from moment to moment every day. It does so more extensively, I think, than any of the other juxtapositional IF or hypertext I’ve mentioned above — and makes me wonder what more could be done in this space.

Resources:

- Word Circuits article by Robert Kendall in 1998, about hypertext testing, from a different tradition of beta-testing and beta-reading.

“A few passages suggest contemporary MUDs” – more than suggest: this is literally the description of the LambdaMOO lounge.

Yeah, huh, she was at Xerox PARC and did some writing projects on LambdaMOO itself: https://people.well.com/user/jmalloy/moopap.html