I began Arcadia – a novel conceived and written for an app – over four and a half years ago when a lot of people were musing about digital narrative. After working my way through three publishers, two designers, four sets of coders and a lot of anguish, I am no longer surprised that few others have done anything about it.

Thus Iain Pears , on why his latest novel is an app and why it took so long to build. His “few others have done anything about it” is characteristically dismissive and makes me grit my teeth. There is so much going on in digital narrative and related fields that it’s challenging to keep up with the variety. What Pears apparently means is that few novelists with London literary agents have done anything with digital narrative, and possibly that he doesn’t regard anything outside that circle as worth checking out. That is his prerogative, but a little more awareness of the world outside might have brought tools to his attention that would have lightened the workload.

, on why his latest novel is an app and why it took so long to build. His “few others have done anything about it” is characteristically dismissive and makes me grit my teeth. There is so much going on in digital narrative and related fields that it’s challenging to keep up with the variety. What Pears apparently means is that few novelists with London literary agents have done anything with digital narrative, and possibly that he doesn’t regard anything outside that circle as worth checking out. That is his prerogative, but a little more awareness of the world outside might have brought tools to his attention that would have lightened the workload.

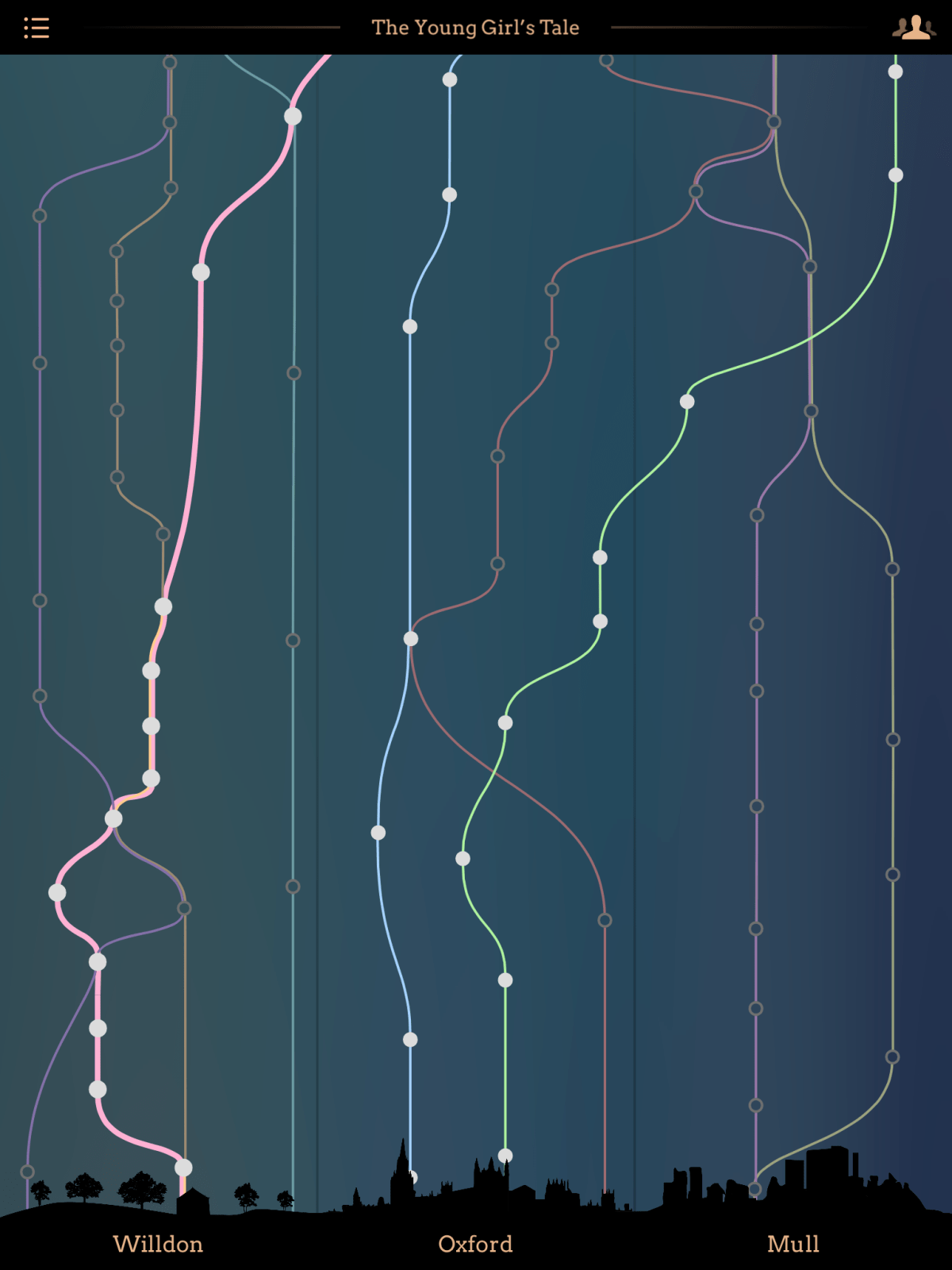

It is true, though, that Arcadia is different in structure, scope, and conception from a lot of other interactive literature. The piece is a series of short scenes about many different characters, together with an app whose narrative map allows the reader to follow one character at a time or leap across time to seek the answers to questions. This puts it in a category with Snake Game and The Strangely-Browne Episode in that it is primarily letting the reader choose a course through the story, not alter the plot itself: it is not linear and the reader does have important agency, but that agency affects the reading experience, not the development of events.

Further, Arcadia takes place in three separate settings — Oxford of the 1950s and early 60s, a fantasy world invented by one of the Oxonian characters, and a technocratic dystopia of the future — though over the course of the plot, the reader may come to question whether these are in fact alternate universes and whether the fictional world is less real than our own. Another reading strategy might be to read all the events in one setting first, then pursue those in another.

*

The app

Pears has said that he wants reviewers to focus on the content of the work and not on its structure, and that he wanted the app to avoid being gimmicky and flashy. It does succeed in being fairly transparent, but I have a few thoughts about it nonetheless, before I go on to the content or the structure of the piece.

The app’s narrative map reveals some intriguing things if you study it carefully. One line splits in two when a character is in two places at once. (This is a story of time travel and alternate universes, after all.) Elsewhere a fresh line comes into being when a new character is introduced to the story. Crises in the story are evident because so many character threads come together and intertwine.

In the reading interface, though, the app downplays these important moments. When you read a chapter whose characters subsequently split up, the page looks like this:

…and you have to swipe sideways in that last quarter of the screen to check out what the alternative continuations might be. It’s understated, even possible to miss. In this particular case it is both striking and narratively important that either of your two next pages will belong to the Young Girl’s Tale, but you don’t see this at a glance. I could see aesthetic arguments for playing this subtle, but I think I myself would have preferred something that more clearly showed what was happening at this moment.

Meanwhile, once you’ve started reading a new chapter, you can’t jump sideways to any of its siblings unless you first go back to the top-level map. That’s something that I often would have liked to do. And if you swipe to go back a page when there are multiple strands leading to where you are, you also don’t get a choice of which backward step to take. At least once, I’m pretty sure I tried to back up to a vignette I’d just been reading but accidentally switched tracks and wound up confusing myself further. So the navigation here, while conforming somewhat to Pears’ declared desire for simplicity, did still miss some functionality I would have liked to have.

*

Routes through the map

There are many, many possible ways to read this — by which I mean not just that the combinatorial numbers are large, but that there are multiple reading strategies one might pursue. Follow one character to the end first? Read about events in one of the settings, then go to a different one? Switch back and forth between strands frequently, to try to get contemporary events at the same time?

There are many, many possible ways to read this — by which I mean not just that the combinatorial numbers are large, but that there are multiple reading strategies one might pursue. Follow one character to the end first? Read about events in one of the settings, then go to a different one? Switch back and forth between strands frequently, to try to get contemporary events at the same time?

I experimented with several of the characters, but soon settled on the story of Angela Meerson, a time-traveling scientist whose experiments in the future apparently precipitate a lot of the rest of what happens — though of course, as always with a time travel story, the question of cause and effect becomes rather tangled.

Once I’d read all of Meerson’s story, I went back and started filling in what had happened to some of the other characters. Other reviews I’ve read don’t center their discussion on Meerson, but focus instead on Professor Lytten (the Oxford man who has written the fantasy story) and on a young woman named Rosie — which seems to bear out Pears’ remark

Minor characters can become major ones at will, and central characters become bystanders equally easily.

In my readthrough, Meerson took on a primacy that she might not have for other readers. I chose to start with her because I thought her understanding of events would be the most authoritative, and would then give me the structure that would let me understand the more subjective, confused, and often emotionally richer experiences of the other characters. Her scenes are also, uniquely, narrated in the first person when she is alone.

I then filled in a lot of the events set in Oxford and in Willdon (the main scene of action in the fantasy universe of Anterwold), and last of all the strands for the characters who remain in Angela’s future world. Here, again, I was chasing the bits of the text that I thought might answer whatever questions I had next.

I can also see, though, why one might start with Lytten, the 1960s don-and-spy living in North Oxford who has designed Anterwold. We first meet him telling his story to a group of Inkling-likes in a setting not obviously distinguishable from the Eagle and Child, though a few years after the historical Inklings had stopped meeting there. He is friends with Tolkien and impatient with Lewis, and his comments on both sound a lot like authorial ventriloquism. Of all the characters, he seems most likely to offer Pears’ own perspective on events.

That these diverse reading approaches work is a tribute to Pears’ meticulous construction. The storyline of each character does make sense read through by itself, though it may appear full of startling coincidences. Each character line does come to an emotional conclusion. But the book is also seeded with hints of what might be found elsewhere. Towards the end of the Willdon section, a character mentions that there is a long story to explain something she has done, and it was immediately evident where I should go look for that explanation. Elsewhere there is a mystery laid out so that you might discover either the culprit or the significance of the act, but not both at once. It remains mysterious regardless of which end is up.

The effect is also down to Pears cheating — or, at least, not quite keeping the implicit promise of the narrative design. You can follow most of the characters from one vignette to another using the narrative map, but there are a few who go uncharted, including one very significant character.

Continue reading “Digital Narratives of Time, Death, and Utopia: Arcadia (Iain Pears) et al”

So instead we have a non-mapped, non-CYOA print book, but one I think might be of some interest to the kinds of people who like IF.

So instead we have a non-mapped, non-CYOA print book, but one I think might be of some interest to the kinds of people who like IF. is a collection of short chapters about city plans and city concepts. It discusses utopian and dystopian visions, cities imagined for other times and environments than our own, the cities we think other cultures would build and the cities that will suit the culture we hope one day to have. It pulls in the writing of architects and urban planners, historians and fantasists and philosophers. It is, among other things, a vibrant celebration of world-building:

, from which there is a quotation on the first page. I’ve also seen reviews comparing it to W.G. Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn

— both books combine a wealth of anecdotal material — but Sebald’s work has a flow and continuity that Imaginary Cities does not always emulate, and his anecdotes (take for instance the business of the the herrings that begin to glow after their death) are selected in service of his greater themes. Imaginary Cities is more of a compendium of curious facts, first collated from a wide range of sources and then organized topically, with quite a lot of the content dedicated to quotation. The result is almost overwhelmingly rich. Individual sentences suggest whole stories and courses of research: