[Yesterday I gave a talk at the Oxford/London IF Meetup. The session was about conversation as gameplay, and also featured Flo Minuzzi of Tea-Powered Games, speaking about their released game Dialogue and their upcoming Elemental Flow. There’s a nice livetweeted thread version of my talk available on Twitter thanks to Florence Smith Nicholls, but I promised also to make a blog post about what I said.

Because the talk was written for an audience that included students, game designers from other parts of the industry, and newcomers to interactive fiction, I included some history of my own work that may be redundant for readers of this blog; there’s also some overlap with a talk I gave in Warsaw last September. However, the material towards the end of this talk is largely new.]

*

The Problem Statement

I want more games to be about human interaction, about the nuances of how people deal with one another, about the kinds of topics that appear in dramatic movies. That’s partly because I’d like to play more games about conversation and social interaction. I’m not as interested in action as a topic, and to be honest I often fall asleep during superhero movies these days.

Meanwhile, as an artist, part of the reason I write games is to explore and interrogate things I don’t yet fully understand. Building procedural systems and seeing how they perform is a great way to explore whether our mental models are correct. How people understand each other (or don’t), how they connect and why, are topics of enduring fascination for me.

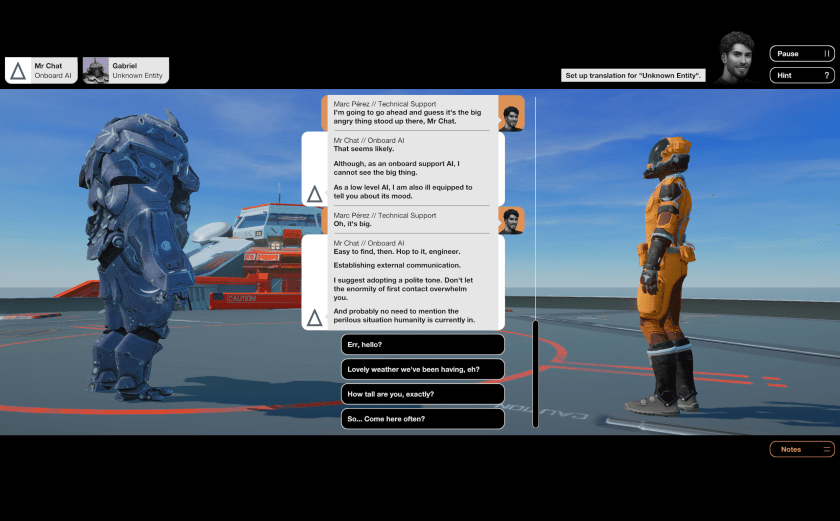

So I want more conversation-rich games. For that to work as I’d like, the conversation needs to be rewarding as gameplay — not just bolted on around gameplay, as it so often is.

When it comes to my own work, I have a few more ambitions and requirements as well:

First, I want it to allow the player to act with intentionality: to lay plans and carry them out. That means that we need some systematic mechanics that the player can learn and manipulate.

For the purposes of this talk, I’m not spending much time on things that are pure branching dialogue trees without ongoing state or clear mechanics. I’ve sometimes written work in that space, and if you’re interested in how to get the most out of a relatively state-light dialogue presentation, I recommend having a look at Jon Ingold’s AdventureX talk about writing sparkling interactive dialogue. But that’s not what we’re looking at today.

[I’ve written more about world model and systematic mechanics for conversation elsewhere.]

Second, I want the resulting mechanic to have good pacing and dramatic qualities — so a mechanic that systematizes conversation but makes it feel very slow, stilted, metaphorical, or hard to manipulate is not what I’m looking for. Some of these can be cool to play, but I myself tend to be looking to write something that has a bit more fluidity.