In a previous post (now several months ago — sorry!) I wrote about visualization strategies for looking at procedurally generated text from The Mary Jane of Tomorrow and determining whether the procedural generation was being used to best effect.

There, I proposed looking at salience (how many aspects of the world model are reflected by this text?), variety (how many options are there to fill this particular slot?) and distribution of varying sections (which parts of a sentence are being looked up elsewhere?)

It’s probably worth having a look back at that post for context if you’re interested in this one, because there’s quite a lot of explanation there which I won’t try to duplicate here. But I’ve taken many of the examples from that post and run them through a Processing script that does the following things:

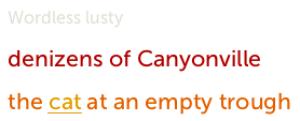

Underline text that has been expanded from a grammar token.

Underlining is not the prettiest thing, but the intent here is to expose the template- structure of the text. The phrase “diced spam pie” is the result of expanding four layers of grammar tokens; in the last iteration, the Diced Spam is generated by one token that generates meat types, and the Pie by another token that generates types of dish.

structure of the text. The phrase “diced spam pie” is the result of expanding four layers of grammar tokens; in the last iteration, the Diced Spam is generated by one token that generates meat types, and the Pie by another token that generates types of dish.

This method also draws attention to cases where the chunks of composition are too large or are inconsistent in size, as in the case of the generated limericks for this game:

Though various factors (limerick topic, chosen rhyme scheme) have to be considered in selecting each line, the lines themselves don’t have room for a great deal of variation, and are likely to seem conspicuously same-y after a fairly short period of time. The first line of text locks in the choice of surrounding rhyme, which is part of why the later lines have to operate within a much smaller possibility space.

Increase the font size of text if it is more salient. Here the words “canard” and “braised” appear only because we’re matching a number of different tags in the world model: the character is able to cook, and she’s acquainted with French. By contrast, the phrase “this week” is randomized and does not depend on any world model features in order to appear, so even though there are some variants that could have been slotted in, the particular choice of text is not especially a better fit than another other piece of text.

Increase the font size of text if it is more salient. Here the words “canard” and “braised” appear only because we’re matching a number of different tags in the world model: the character is able to cook, and she’s acquainted with French. By contrast, the phrase “this week” is randomized and does not depend on any world model features in order to appear, so even though there are some variants that could have been slotted in, the particular choice of text is not especially a better fit than another other piece of text.

This particular example came out pretty ugly and looks like bad web-ad text even if you don’t read the actual content. I think that’s not coincidental.

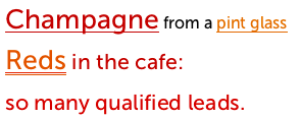

Color the font to reflect how much variation was possible. Specifically, what this does is increase the red component of a piece of text to maximum; then the green component; and then the blue component. The input is the log of the number of possible variant texts that were available to be slotted into that position.

Color the font to reflect how much variation was possible. Specifically, what this does is increase the red component of a piece of text to maximum; then the green component; and then the blue component. The input is the log of the number of possible variant texts that were available to be slotted into that position.

This was the trickiest rule to get to where I wanted it. I wanted to suggest that both very high-variance and very low-variance phrases were less juicy than phrases with a moderate number of plausible substitutions. That meant picking a scheme in which low-variance phrases would be very dark red or black; the desirable medium-variance phrases are brighter red or orange; and high-variance phrases turn grey or white.

Here “wordless” and “lusty” are adjectives chosen randomly from a huge adjective list, with no tags connecting them to the model world. As a result, even though there are a lot of possibilities, they’re likely not to resonate much with the reader; they’ll feel obviously just random after a little while. (In the same way, in the Braised Butterflied Canard example above, the word “seraphic” is highly randomized.)

Finally, here’s the visualization result I got for the piece of generated text I liked best in that initial analysis:

We see that this text is more uniform in size and color than most of the others, that the whole thing has a fair degree of salience, and that special substitution words occur about as often as stressed words might in a poem.

*

There’s another evaluative criterion we don’t get from this strategy, namely the ability to visualize the whole expansion space implicit in a single grammar token.