Last year I wrote about the way Gone Home is mostly backstory but doesn’t yield to thematically directed exploration. I talked then about wanting to see more games of research, pieces where the player could make guesses about where things were going and then test them out.

Sam Barlow’s Her Story accomplishes that nebulously-framed wish of mine, and brilliantly so.

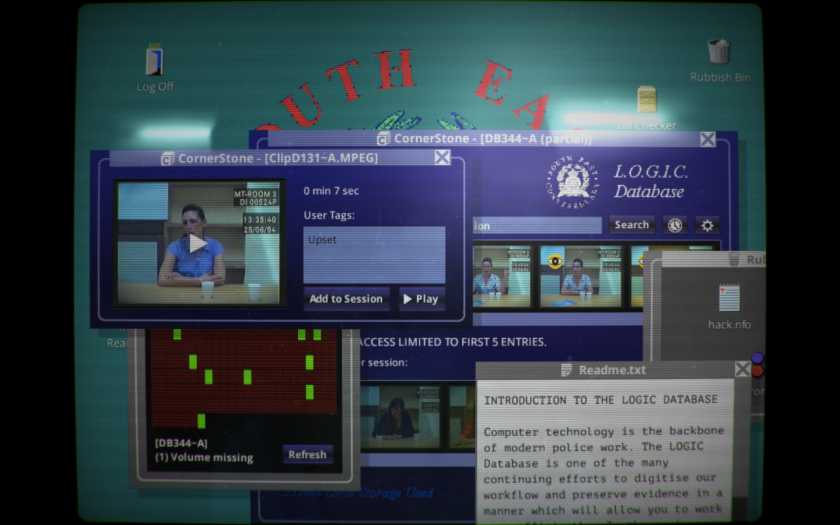

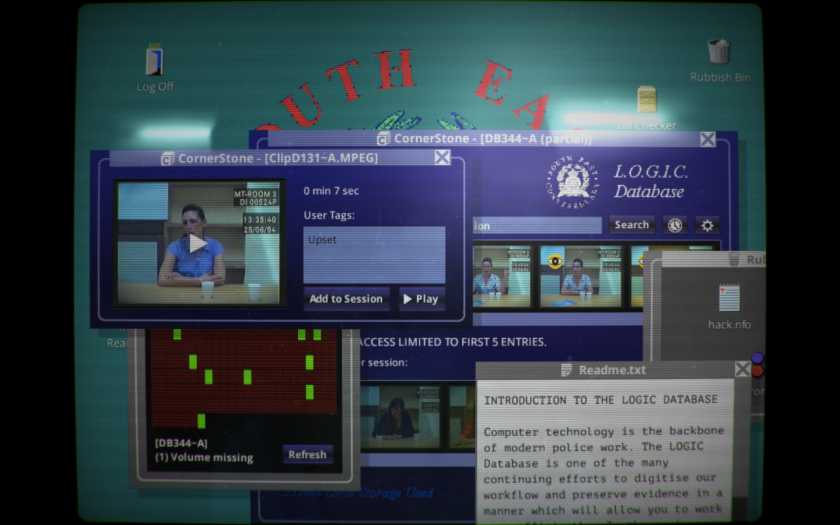

The idea is apparently straightforward: the protagonist has access to a database of video snippets taken from the interrogation of a woman involved with an apparent murder more than 20 years ago. The video snippets all have searchable subtitles, which means that if you look for a word that is spoken in one of these snippets, you can bring it up. What you can’t do is watch all the snippets in order; and if more than five snippets are associated with a particular keyword, then you can’t access those after 6. (This prevents the game from being too easily solved by someone who latches onto key names early on.)

As a police filing system this is perhaps not very practical, but it makes for a highly engaging game. One starts with a prompt, “murder”, which turns up several snippets with which to get started. From there, it’s a matter of thinking of new keywords to enter. Sometimes the keywords are names or places mentioned in one video that are obviously important. Sometimes I reached them by association or guesswork instead: if one hears about a death, it’s reasonable to want to know what happened at the funeral, for instance. And, of course, the same snippets of video may be reached by several different routes, so there’s less of a premium on exhaustiveness than in something like Toby’s Nose (but perhaps more than in the intentionally unmappable daddylabyrinth). It also feels less controlled and gated than Analogue: A Hate Story.

The game also has a second level of robustness, namely, it’s not necessary to see absolutely every snippet in order to work out what happened. 80-90% is probably sufficient. Personally I had a pretty good idea of what had happened by the end of a couple of hours, though I kept playing for a while longer in an increasingly quixotic mission to find the last remaining bits. I failed to get them all, but I reached a point where I felt pretty satisfied.

It’s massively daring to tell your story in whatever order the player happens to stumble upon — and yet my experience and the experience of every reviewer I’ve read so far was that the narrative order they experienced was compelling and memorable. After playing through this myself, I brought it along to an interactive fiction meetup and watched another group of people play: they saw the story unfold in a totally different way than I did, but it still worked. (They were also so fascinated with the game that we stayed on that for two hours and never moved on to other activities.)

There are a couple of features of the snippets themselves that make this scheme work. First, they’re telling a story that is very complicated (so there’s quite a lot to find) but differently shaped from what you might initially expect (so you’re not just filling in some sort of Motive/Opportunity/Method chart).

Second — and this is a reflection of both writing skill and the quality of the acting — they contain multiple kinds of information. In the earliest phases of the game, the player is just trying to get a sense of the key people and places in the story, scanning the snippets for names to build up a who’s-who. Then one starts comparing new snippets to old ones, looking for factual discrepancies and implications. Later, after the shape of the story has started to emerge from the mist, they start to be readable for emotional hints as well. There are details — visual details, verbal details, tones of voice and choices of imagery — that only take meaning after the player knows quite a lot about what is going on. And that is why the same snippet can still function well in the building of the narrative regardless of whether you see it as almost your first pick of the game or not until quite late.

I’d like to talk about the actual content a bit; however, any discussion of the story itself is of course massively spoilery, even more so for this work than for most games. So I’m going to put that behind a tag.

However, if you’re reading this review to find out whether I think it’s worth playing: yes, absolutely. If you’re a parser IF fan from the old days, you probably remember Sam Barlow from Aisle, a one-move game that is still one of my go-to pieces for introducing new players to parser IF despite the fact that it was written in 1999 — and you may find that the game has more in common with parser IF than you might have thought possible. If you’re a student of experimental narrative forms, this is a smashing example that people will be discussing for some time, and you should know about it. If you’re more of a mainstream indie game enthusiast, you’ve probably already seen the collection of positive reviews Her Story has racked up elsewhere, but in case you haven’t: this is not only a fascinating experiment, it’s also a solid, suspenseful gaming experience that kept me on the edge of my seat.

And the disclaimer: I bought this game in preorder, but Sam then sent me an advance key so that I could play early and review it.

Go play it before you read anything else I have to say. PLAY IT PLAY IT.

Continue reading “Her Story (Sam Barlow)”

The Beginner’s Guide is a new game by one of the creators of The Stanley Parable. The premise is that Davey had a game-developing friend called Coda who wrote a bunch of small, arty games between 2008 and 2011, and Davey wants to walk us through these, showing the progression of the games and of his own relationship with Coda. He provides a voice-over that narrates everything we encounter. In some cases the discussion focuses on the design ideas and in some cases it touches lightly on the technical work that went into making a level.

The Beginner’s Guide is a new game by one of the creators of The Stanley Parable. The premise is that Davey had a game-developing friend called Coda who wrote a bunch of small, arty games between 2008 and 2011, and Davey wants to walk us through these, showing the progression of the games and of his own relationship with Coda. He provides a voice-over that narrates everything we encounter. In some cases the discussion focuses on the design ideas and in some cases it touches lightly on the technical work that went into making a level.