Tonight (June 20), the London IF meetup is going to play In Case of Emergency, a game delivered mostly through the format of physical props.

The prospect of this has me thinking again about narrative told through objects, a topic I sometimes come back to here: everything from the work of the Mysterious Package Company through to the story-in-a-suitcase designed by Rob Sherman.

Infocom, of course, had its tradition of “feelies,” part copy-protection device and part souvenir, distributed with games: these consisted of printed manuals, letters, evidence dossiers, coins, pills, letters, and whatever else they could think of. Wishbringer came with a plastic glow-in-the-dark “stone” which represented the eponymous magic object of the game, and let me tell you that when you are eight years old a glowing plastic rock is pretty special. Jimmy Maher frequently mentions them in his Digital Antiquarian writeups on these games. For a while in the 90s there was a tradition of sending people feelies as a reward if they registered shareware interactive fiction, but shareware also died out as a way of distributing IF.

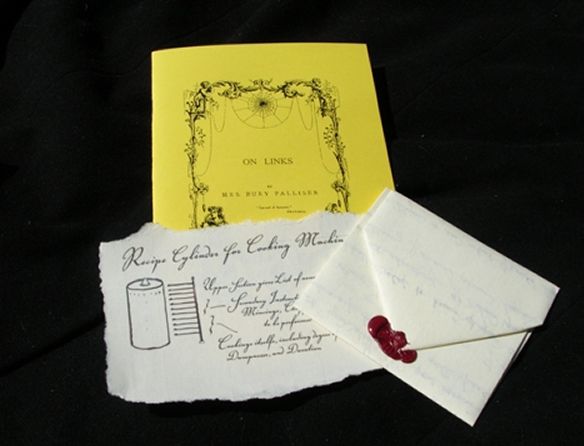

This captured my imagination, and for Savoir-Faire, I made a limited feelie run just for people who pre-ordered via rec.*.int-fiction:

It consisted of some supposedly historical documents and some modern ones:

- a customized-to-the-recipient letter about the history of the objects, from a modern professor at the University of Pennsylvania (where I was at the time supposed to be finishing my PhD, but was actually procrastinating with projects such as this one);

- a reprinted pamphlet about the Lavori d’Aracne, the magic system in the game;

- a letter from one of the game’s characters to his daughter, sealed with sealing wax and designed not to be read until the end of the game; and

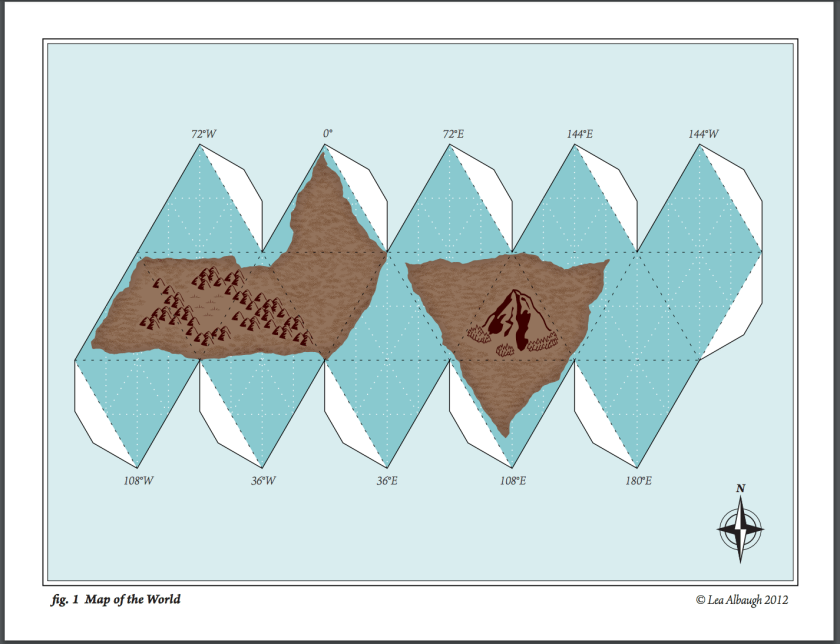

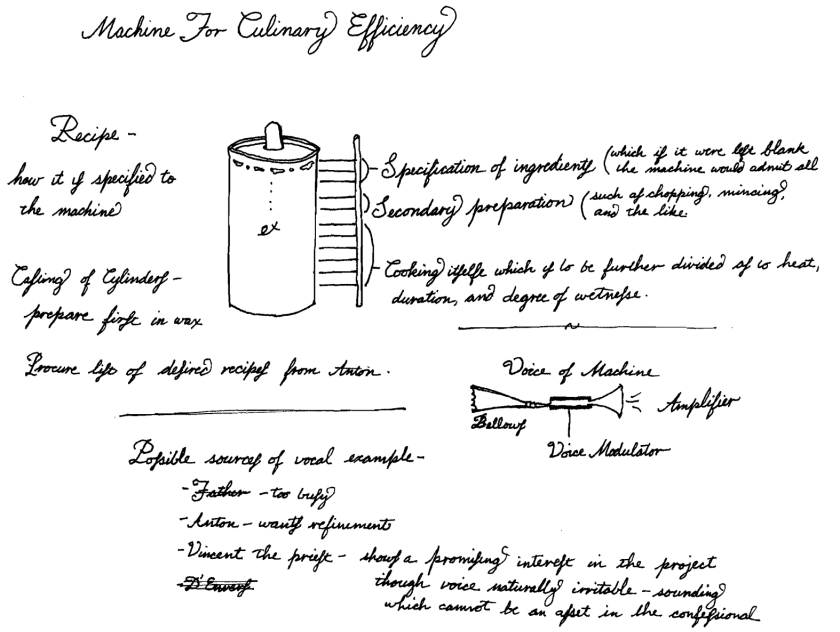

- a scrap of paper carrying what was supposedly a magic machine design by another character:

By the standards of, say, Punchdrunk, these weren’t impressive objects (you can see a scan of the full set in this PDF), but given my skills and abilities at the time, they were the best I could do. The pamphlet was based on some reprints I’d found of little etiquette manuals from the late 18th and early 19th century. The letter was handwritten with a fountain pen that I bought for the purpose — an expensive investment given my grad student poverty — and I tried to school myself in contemporary handwriting styles, though as you can see, I am not destined for a career in forgery any time soon.

As for the machinery design, for the very earliest purchasers, that was written on actual period paper that I bought from an online ephemera reseller, and I’ve always felt slightly bad that I tainted real 18th century paper, a limited resource no doubt salvaged from some antique desk drawer, with my very much 21st-century scribbling. (Later on, I handwrote on more boring paper, and later still I digitized and printed the thing with a suitable font.)